During a hearing last month in the case of Barrett Brown — a jailed journalist known for his advocacy of the hacktivist collective Anonymous — the Justice Department (DOJ) entered into the court record 500 pages of evidence containing e-mails and chat logs that it claimed would demonstrate “relevant conduct” to his sentencing. Yesterday, the Daily Dot reported that “the FBI may have gleaned tens of thousands of pages of conversations from Brown’s hard drive, potentially revealing his daily contact with hackers and other sources who ostensibly believed they were speaking with the journalist and activist in confidence.”

This evidence, along with other facts from Brown’s case and that of his source Jeremy Hammond, shows the importance of digital security in the age of surveillance. How would Brown’s case have looked if he had used encryption and other security methods? Potentially a lot different.

In summer 2012, I asked Brown why he didn’t use encryption tools such as OTR (Off The Record) encrypted chat. Even while acknowledging that he knew he was “under relatively harsh surveillance by the FBI,” he told me the following:

I generally don't try to hide my communications these days, as I'm not often dealing with people who aren't sufficiently hidden or who have anything truly secret to tell me… I normally would, but my work right now is about 100 percent revolved around spreading info that's already out. I don't consider myself a criminal in any shape or form and never have, and refuse to 'hide' from a government I see as illegitimate.

He later explained that he wanted to keep an exculpatory record for his own protection in case he was ever misrepresented or accused of anything he didn’t do, and that he was conducting research for a book about Anonymous that had been sold to Amazon.com, so would need to refer back to events. He wasn’t totally adverse to the idea of protecting his communications via encryption, but seemingly lacked the technical skills to set it up.

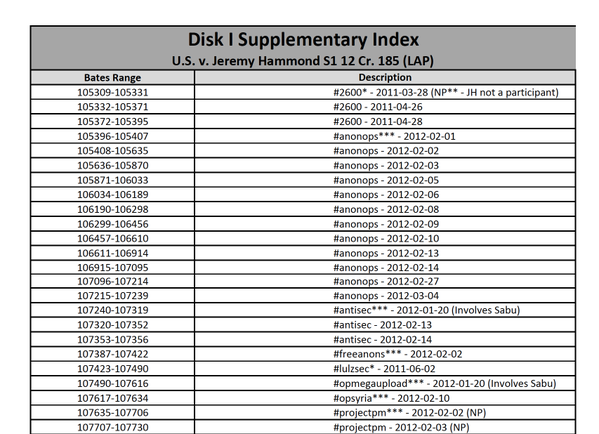

A source relationship with convicted Stratfor hacker Jeremy Hammond, also known by the nicknames “o” and “burn”, would in time see Brown charged with a felony accessory CFAA (Computer Fraud and Abuse Act) count for which he’ll be sentenced tomorrow. That charge is based on his alleged attempt to contact Stratfor representatives on behalf of Hammond and offering to redact sensitive e-mails before they were released.

Transport encryption (SSL)

In Barrett Brown’s initial sentencing hearing last month, a prosecutor asked about Jeremy Hammond’s consistent demand that Brown set up SSL (Secure Sockets Layer), which can be used to secure connections to IRC (Internet Relay Chat) servers, in addition to websites. In fact, chat logs which became part of Hammond’s case and are believed to come from Brown’s computer, show that Hammond asked Brown whether he had set up SSL no less than four times in a span of two months — with Brown invariably procrastinating on his promises to set it up or to get someone else to do it for him:

[22:03] you _have_ to start using SSL

[21:42] ssl yet?

[21:42] gotta get on that

[18:26] Still no SSL I see.

[14:31] yes you still not on SSL?

[14:31] you need to get on that shit

[12:58] you should really use SSL

These exchanges aptly illustrate the notorious usability challenges of encryption. If Brown had enabled SSL while connecting to chat servers, it may have shielded his private conversations from surveillance by third parties. For further protection, they could have used OTR to encrypt end-to-end, removing the server's ability to eavesdrop as well.

Minimize retention of logs and stored data

This doesn't preclude the possibility, however, that either participant could be logging their chats, thus creating a record that could be obtained later. The unfortunate truth is that keeping unencrypted records of chats on your computer can inevitably result in them being used against your sources and correspondents if seized, which is also what happened in Brown’s case.

Michelle Garcia, reporting for The Intercept, voiced the opinion that these chat logs were being spun to fit the government's agenda: “The evidence that was discussed was often selectively disclosed by prosecutors, who tore from their original context lengthy chats and emails to depict Brown as a malicious hacker rather than a journalist.”

In practice, many journalists need to keep logs of certain conversations with sources — so in these cases, the logs should always be moved offline and stored on an encrypted drive. The same guidance applies to e-mail archives and other documents save on your computer. If you’re working on a sensitive story then you should reduce the material you keep to only that which you absolutely need. Plus, deleting files actually does not completely erase them from your hard drive, so you need to practice secure deletion which you can learn more about here.

But if such logs are not needed to report the story, journalists should ensure that logging is turned off inside the messaging programs they use. Many clients have logging enabled by default, but it can usually be disabled within the preferences or options.

Use full disk encryption

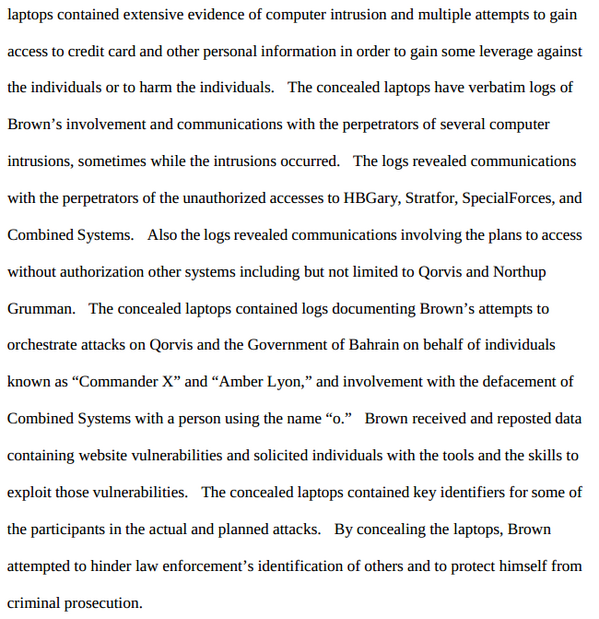

With the FBI closing in, Brown has said he tried to protect his sources by taking his laptops to his mother’s house, which required them to apply for a second warrant. Brown then hid the computers in a kitchen cabinet. Needless to say, it didn’t work, and the devices were seized. Those actions later triggered obstruction of justice charges for both Brown and his mother.

In general, journalists should always protect others from gaining access to their computer when it's powered off by using full disk encryption (a method of encrypting all of the information stored on your hard drives). If their computer is ever seized by law enforcement, the authorities—at least in the US—would have to attempt to compel the journalist to enter a password, which can be challenged in court. This also allows journalists to raise reporter’s privilege claims on certain information before the government gets a hold of it, and at least gives them a chance to narrow the scope of the government’s demands.

Among other things, Barrett Brown was intrepidly investigating capabilities like advanced data-mining, predictive analytics, and social media monitoring. After Snowden and the exposure of the NSA’s collection posture, and retrospective of his case, Brown’s prior approach to digital security seems misguided. It’s hard to avoid the perception that it would have helped minimize the injustice he was bound to face to simply have been more stringent with his security. But his case offers object lessons to journalists on the importance of practicing good operational security by using encryption and minimizing logs.

Full disclosure: In addition to working for Freedom of the Press Foundation, Kevin Gallagher runs Free Barrett Brown, a legal defense fund and advocacy organization.