This article was republished with permission from the Education Writers Association. It has been lightly edited for style and consistency.

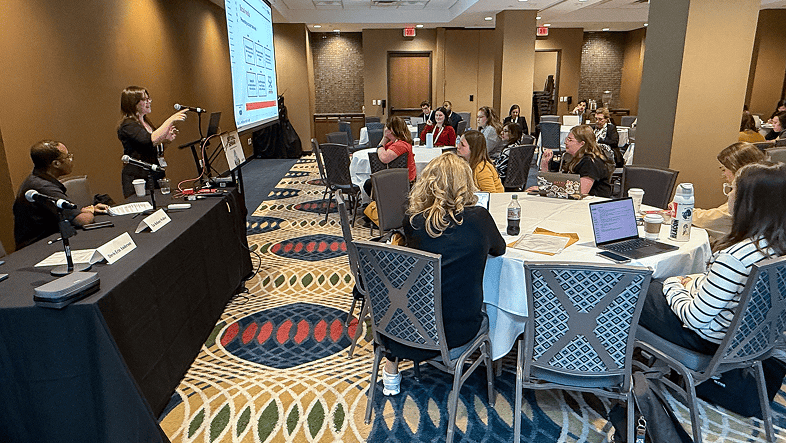

A question many journalists are asking themselves in today’s shifting digital landscape: How can I protect myself and my information online? That was also the focus of a session during the Education Writers Association’s 2025 National Seminar in St. Louis last May.

“We want to empower you with strategies and resources to protect yourself and others from hacking, doxxing, impersonation, and other abusive tactics,” said Tat Bellamy-Walker, program manager, digital safety and training resources (media) at PEN America. And the hourlong conversation did just that: Journalists from across the nation in attendance walked away equipped with resources and next steps to protect themselves online.

If you weren’t able to make the St. Louis session, don’t fret — you can still learn the takeaways and tips to protect yourself digitally.

Speakers

Moderated by EWA’s public editor, Emily Richmond, the session featured:

- Tat Bellamy-Walker, program manager, digital safety and training resources (media), PEN America; co-director of the Trans Journalists Association’s Peer Career Network; previously held the role of communities reporter at The Seattle Times

- Davis Erin Anderson, senior digital security trainer, Freedom of the Press Foundation (FPF)

Top takeaways

Online harassment is common. In a 2021 survey conducted by the Pew Research Center, 41% of Americans reported that they had experienced some form of online harassment. Women, people of color, and LGBTQIA+ individuals cited being targeted for their identities, and they experienced harassment online at a disproportionate rate compared to men, white people, and straight people.

A survey published by the Anti-Defamation League in June 2024 noted that of all the marginalized groups surveyed, LGBTQ+ individuals experienced the most harassment, with an increase in physical threats from 6% to 14% over the previous year.

A 2021 report by the EWA “found that roughly 60% of education reporters have been threatened or harassed by their audiences or sources, and most education journalists have been harassed either through email, through Twitter or X, and even Facebook,” Bellamy-Walker said.

Get comfortable not knowing any of your passwords. “Passwords should be unique, random, and long. That is ‘URL’: unique, random and long — very, very important,” Anderson said. “You want to make sure there’s a one-to-one ratio between your account and your password. Passwords should never be used twice, ever.” Instead, use a password manager to create and store unique passwords for you. Read more below.

More of your information might be online than you realize. Addresses and phone numbers can be easy to find, especially if you’ve been on social media a long time.

“A lot of times, when folks are going through your old post, this is social media-wise, now they can screencap it and put it on the darknet, where all the trolls gather to watch their attacks,” Anderson explained.

But still, there are tools to help remove your information, such as DeleteMe, EasyOptOuts, Kanary, or Optery.

“We have power.” “The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second-best time is today. The best time to not say things online was 20 years ago in my case; the second-best time is today,” said Anderson, adding that we can reduce harm and others’ abilities to track down our information by using tools that are readily available.

Tips and strategies

Dox yourself. Doxxing, which is the unauthorized publication of personal information, like addresses and contact information, is a common form of digital harassment. But the act of doxxing yourself doesn’t involve posting your own personal information; it’s the opposite. Search for your own name across search engines and see what comes up, and try a reverse image search. Then, you can take steps to opt yourself out of websites, often run by a data broker. Use The New York Times Open guide to walk yourself through the process.

Use a password manager. Password managers, such as 1Password, Bitwarden, or Dashlane, hold all of your passwords in one place and keep them secure. The managers can curate unique passwords for each of your accounts, so you don’t have to come up with them yourself or remember each character. You can also use Google Passwords Manager or iCloud Keychain. The password manager 1Password is free for journalists, which you can set up here.

Be aware of what you’re posting and when. Avoid geographical location tags, and wait to post about a trip or a vacation until after you’ve left and returned home. When posting photos from your home or a private space, make sure to double-check there’s nothing in the photo that could give away your location, such as a street sign, a house number, or unique building features.

Set up two-factor authentication. This next step, also sometimes known as multi-factor authentication or two-step verification, creates a unique numerical code every time you, or someone else, tries to access one of your accounts. You can use apps, such as Google Authenticator, Microsoft Authenticator, or Yubico Authenticator, to access these codes.

Housekeeping of old posts. Consider taking a walk down memory lane to revisit your old Twitter (X), Instagram, and Facebook accounts and delete old tweets and posts that might reveal information you no longer want online.

Adjust account privacy settings. This can include setting your social media accounts to “private” rather than “public,” changing who can send you friend requests, and adjusting who can see your personal information and activity.

Talk with your editors. Before abuse happens, chat with your editor about expected social media use related to your work. (For example, are you expected to push out your stories on a personal Instagram account?) Additionally, ask what resources your newsroom offers to protect its journalists from harassment.

“We know that documenting the abuse can feel very traumatic for folks, so we also recommend doing this with a friend or a colleague to help you, or asking your editor to also help you with documenting the abuse,” Bellamy-Walker said. “And what’s so important about documenting is that it can help you identify patterns in the abuse and can alert you on whether the abuse is escalating, which is really important.”

Mistakes to avoid

Scanning random QR codes. Curious about a QR code on a telephone pole in Manhattan that supposedly leads to a local band’s website? Don’t scan it. The links can be malicious, from bad actors, leading you to a malware attack site, for example.

Deleting abusive emails or texts. If you’re a victim of online abuse or harassment, save the URL, as well as screenshots or PDFs with dates and time stamps of the abuse. This will be helpful should you choose to take legal action or file a police report.

Sharing personal information through an unsecure platform. If a source wants to share something personal over a messaging app, opt for a platform like Signal, which offers end-to-end encryption on both texts and calls. For email, Proton Mail is also end-to-end encrypted between users who both have a Proton Mail account. You can also set up a phone number with Google Voice to avoid sharing your personal cellphone number.

Using the same password. Do not ever use the same password twice. If a hacker gets hold of one of your passwords and it’s used for more than one account, that means each account with the same password is compromised. Even though you might have hundreds of accounts — from social media to banks and news subscriptions — make all of them different.

Resources

- AEGIS Safety Alliance offers free identity- and trauma-centered safety training for journalists.

- Consumer Reports’ Safety Planner is a free digital security planner.

- FPF provides resources and guides to digital safety for journalists.

- International Women’s Media Foundation offers “A Guide to Protecting Newsrooms and Journalists Against Online Abuse,” as well as several other comprehensive safety guides and tips.

- PEN America Online Harassment Field Manual provides strategies for defending yourself and others.

- PEN America Digital Safety Snacks offers step-by-step videos for online protection against digital harassment and abuse.

- Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press provides reporting guides to help advance press freedom.

- The New York Times’ self-doxxing guide details a number of how-tos.

- The New York Times/Wirecutter “Back Up and Secure Your Digital Life” provides both physical and digital safety resources.

Trans Journalist Association offers a slew of guides and resources to help a gender-expansive journalist protect themselves online.