It’s nearly impossible to gauge the full impact of harassment of the press. How do you measure the stories that go untold because a journalist felt intimidated? How do you quantify the corruption that won’t be exposed because sources are afraid to talk? When the impact of threats is silence, there’s no way to assess what we’re missing.

A threat to press freedom is an assault on our right to know.

A new report from the Committee to Protect Journalists tries to capture the invisible impact of the Obama administration’s troubled relationship with the press. The report, authored by Leonard Downie Jr., former executive editor of the Washington Post, and CPJ’s Sara Rafsky, is the most comprehensive look at how the Obama administration’s actions have deeply damaged press freedom and the public’s access to information.

The need for a major course correction

For those who have followed the administration’s policies, court cases and actions related to leaks and the press, the report doesn’t contain a lot of new information. What it does is weave together each of the cases and strategies the administration has pursued, surfacing key themes and illustrating that these examples are not aberrations, but part of a coordinated strategy. Presenting this bigger picture reframes the debate over press freedom in America and reminds us that it is not enough to tinker around the edges — we need to demand a major course correction.

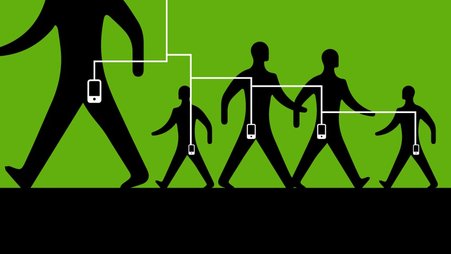

Downie and Rafsky connect the dots between the Obama administration’s leak investigations and policies, surveillance programs, increased secrecy and use of social media to speak directly to people and “evade scrutiny by the press.” All of this is punctuated by the interviews Downie conducted with journalists. Hearing from journalists in their own words, about the challenges they have faced, and the concerns they have, brings home the seriousness of the crisis in press freedom.

A shift in power

New York Times National Security reporter Scott Shane captured it best when he told Downie that sources are now “scared to death” to even talk about unclassified, everyday issues.

“There’s a gray zone between classified and unclassified information, and most sources were in that gray zone. Sources are now afraid to enter that gray zone,” Shane said. “It’s having a deterrent effect. If we consider aggressive press coverage of government activities being at the core of American democracy, this tips the balance heavily in favor of the government.”

That shifting balance of power is one of the critical takeaways from the CPJ report. Through administration-wide efforts like the “Insider Threat Program,” which encourages federal employees to monitor the behavior of their colleagues, to National Security Agency surveillance to the Justice Department’s seizure of phone and email records, the Obama administration has marshaled incredible amounts of institutional resources toward efforts that erode press freedom and challenge newsgathering.

“The administration’s war on leaks and other efforts to control information are the most aggressive I’ve seen since the Nixon administration,” Downie writes. “The 30 experienced Washington journalists at a variety of news organizations whom I interviewed for this report could not remember any precedent.”

White House spokesman Jay Carney shrugged off reporters’ concerns as a “natural tension” between government and journalists. In his discussion with Downie he pointed to recent leaks, arguing “The idea that people are shutting up and not leaking to reporters is belied by the facts.” This, of course, ignores the fact that the administration often uses sanctioned leaks and unnamed sources to push their agenda in the press.

The report is a profoundly important addition to the debate about press freedom, but the scope of its inquiry is limiting. In focusing on the Obama administration, Downie examines in depth the various cases of journalists who have been caught up in federal investigations and the actions of federal agencies only. As such, the report is not a full accounting of the state of press freedom today. A more comprehensive analysis of troubling state bills, worrisome court cases and the alarming spike in journalist arrests and harassment by police would help give a fuller picture.

In addition, the journalists implicated in the cases Downie reports on are all from mainstream media organizations like the Associated Press, Fox News and the New York Times, and most of his interviews are with Washington editors and reporters from major newsrooms. I was left wondering how the Obama administration’s adversarial relationship with the press has impacted smaller newsrooms, freelance journalists, independent bloggers and even citizen journalists.

The Committee to Protect Journalists has led the way in looking at the impact of threats to press freedom and freedom of expression on digital journalists and citizen reporters abroad. I hope that this report can be a starting place for CPJ to expand its inquiry to assess the threats and challenges facing all kinds of journalists in the U.S.

It is notable that, in their recommendations at the end of the report, CPJ calls on the Obama administration to “advocate for the broadest possible definition of ‘journalist’ or ‘journalism’ in any federal shield law.” The law must “protect the newsgathering process, rather than professional credentials, experience, or status, so that it cannot be used as a means of de facto government licensing.” While CPJ focuses here on the need for a shield law, this recommendation should apply to any law or guideline the administration implements. The shield law is important not only for how it defines a journalist but also for the precedent it could set for future press freedom decisions.

The CPJ also advocates for guaranteeing journalists won’t be prosecuted for receiving or reporting on leaks, ending the use of the Espionage Act to prosecute those who leak information to the press, improving transparency about NSA surveillance, enforcing revised Justice Department guidelines, ending the use of overly broad secret subpoenas, strengthening the administration’s adherence to the Freedom of Information Act and greater openness regarding government activities.

It’s remarkable that we have to ask for these basic protections and reassurances from our government, but the CPJ report makes clear that we cannot take press freedom for granted. This report should be a starting point for a much larger discussion that brings together journalists of all kinds, with policymakers and citizens to talk through the challenges, questions and concerns about press freedom in our networked, digital age. We are facing a fundamental and coordinated shift in how our government and press interact — and it’s not enough to respond to each attack in isolation. We need to launch a proactive effort to reassert the centrality of a free press in our democracy.