Interviewing incarcerated people

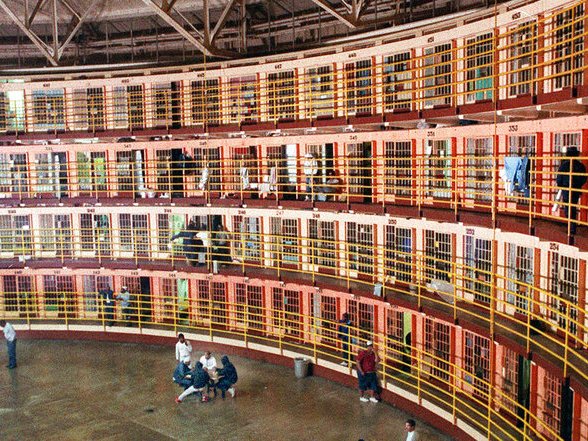

The American incarceration system is a behemoth.

Around 1.9 million people in the United States are locked up in jails, prisons, immigration detention facilities, and other confinement centers. Federal, state, and local expenditures on corrections amount to more than $81 billion each year. Legal costs, criminal policing, and assorted other fees, like bail payments and prison phone call fees, end up costing taxpayers and families an additional $100 billion annually.

But despite its size and scope, the incarceration system is in many ways invisible. Its facilities operate outside the public eye and with less oversight than other governmental entities. And information about carceral institutions is closely guarded by corrections agencies that have a range of ways to restrict public access and block reporting efforts.

These barriers make covering stories about carceral facilities and incarcerated people different from many other types of journalism. As a reporter on this story, you will face logistical challenges that impede your ability to communicate with sources and verify information as you navigate a maze of bureaucracy.

While this guide is not intended to provide a comprehensive blueprint for all the obstacles you may face as you report on incarceration, it will offer broad insights into some common problems you will encounter and how to overcome them. And we hope it’s a reminder that facing these challenges is worth it in the name of transparency on this consequential story.

First, in Part 1, we’ll discuss the challenges of interviewing incarcerated people. Then, in Part 2, we will discuss how to handle barriers to obtaining documents and information.

Know the risks, share the risks

Many incarcerated people have no experience speaking with reporters. So when talking to someone behind bars, be sure to share as much detail as possible about your project, the scope of your reporting, and how their voice will be used in your story.

Be sure to define any journalistic terms you’re using, explaining what you mean, for instance, by “off the record” or “on background.” If anonymous sourcing is an option for your project, offer it at the beginning of an interview to encourage people to speak with you.

Even in cases where your source is comfortable being identified, be cautious about including names or details that might identify other incarcerated people and subject them to potential retaliation, whether by prison and jail officials or other incarcerated people.

Explain the conditions of your conversation to build trust so that the incarcerated person will not pull out of the project once you are closer to publication. Ensure they understand the risks they’re taking by talking to a journalist and are willingly taking those risks. Keep checking in throughout the reporting process to be certain this doesn’t change.

Be aware that jails or prisons may retaliate against those accused of causing problems — such as by unsanctioned communication with media. Retaliation can result in an incarcerated person spending time in solitary confinement, being moved to a facility further from family, or having their cell raided by corrections officers. Officials may also retaliate by confiscating devices or other means of communication. Incarceration facilities and departments could even trump up disciplinary charges to justify this conduct.

Be aware that jails or prisons may retaliate against those accused of causing problems — such as by unsanctioned communication with media.

You should also consider whether you are adequately protecting the identity of anonymous sources. Keri Blakinger, an investigative reporter who covers the criminal legal system, noted that small details you might consider innocuous, like the background of a photo taken with a contraband cellphone, could reveal the identity of someone who wishes to remain anonymous.

“When it comes to things like photos and videos, the biggest question I ask myself is, ‘Will this identify the source?’” Blakinger told In These Times. “This means asking yourself, ‘Is this photo of inedible-looking prison food with mold on it going to identify the unit that it came from, and if prison officials can identify the unit, is that sufficient for them to identify the person who took the image? Will they identify how the image got to me and any intermediaries involved? Will the source face consequences? Are they OK with that?’”

If you are communicating with incarcerated people using contraband cellphones, you should ask before publishing the method of communication. Indicating that your contact has a prohibited device can lead to repercussions. If the source sends you a photo, make sure to clarify whether or not you can publish or describe it.

Access is allowed, but can be restricted and erratic

The First Amendment covers journalists’ ability to report on incarceration facilities, but two 1974 Supreme Court rulings determined the press has no privilege beyond that of the general public to talk to people who are incarcerated.

This means that incarceration agencies and facilities can invoke a series of restrictions to impede journalists’ access and ability to do their jobs. Often these restrictions will be presented as measures to ensure the operational security of staff and incarcerated people.

These restrictions can mean that in-person interviews may be ended by prison or jail staff at any time, that prison or jail staff can select who journalists may talk to, or that interviews may be severely time-restricted.

If general visitors (like family members and friends) are prohibited from using cameras or recording devices at an incarceration facility, the facility may forbid reporters’ ability to bring those items into the facility as well. Facilities may also legally deny media members the right to interview particular incarcerated people. However, the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press notes, “Even though courts have rejected a First Amendment right to interview specific prisoners, most states have statutes or prison rules allowing for some type of access.”

Even so, some states have created enormous barriers to speaking with incarcerated people. Last year, the South Carolina Department of Corrections issued a press release saying that people incarcerated in its system “are not allowed to do interviews.” The ACLU sued the state over that policy in February 2024.

If you are denied the right to an interview, you should ask for a copy of the regulation that dictates access to determine whether the agency is violating its own policy.

Visits require time, jumping through hoops

Even once granted access, visits with incarcerated people are often difficult to arrange and require significant lead time. Many states have online instructions for scheduling a media visit and gaining approval for an in-person interview, or require you to contact the agency’s public information officer.

Media visits in Texas prisons, for example, require at least two weeks’ notice. You will only have an hour for the interview. In California, the subject must send you a visiting questionnaire, which the state corrections department may take approximately 30 working days to review and approve.

Once you gain approval, you will have to schedule a date and time for a visit. This visit could be abruptly canceled for a range of reasons, including facility lockdowns, that the person you want to interview has been subject to discipline by corrections officials, or because someone harmed by the offense that led to your source’s imprisonment has protested the interview.

Journalists exposed serious health and safety concerns at the infamous “F House” in Illinois' recently closed Stateville Correctional Center.

Some states place stringent restrictions on what you can bring into facilities and bar equipment like audio recorders. In California facilities, cameras and recording devices are not permitted, though the agency says it will provide pencil, pen, and paper “as needed.”

Policies around in-person interviews of those who are incarcerated can also be changed abruptly. In 2020, Arizona reporter Jimmy Jenkins was surprised to discover that the state’s corrections department had suddenly altered its media policy and now only permitted reporters to communicate with incarcerated people via paper mail.

Last year, an incarcerated Texas journalist was scheduled to be interviewed by another reporter. Though the state prison agency had previously approved the in-person conversation, the department revoked that permission prior to the meeting. The ombudsman explained via email that the interview had been canceled “due to victim protest.” The scheduled call was not related to the charges that led to the journalist’s incarceration.

Multiple means of (monitored) messaging

Beyond visits, there are other ways to contact incarcerated people. As with in-person visits, though, you should assume that phone calls, messages sent through electronic systems, and regular mail are being read and monitored by corrections officials.

All forms of communication with incarcerated people can be disrupted and be subject to unpredictable delays. While physical letters in some cases previously served as a work-around to unreliable phone and messaging systems, a number of jurisdictions have taken steps in recent years that alter how incarcerated people receive mail.

At least 14 states have started delivering scanned versions of physical mail sent to incarcerated people. (Though corrections officials have claimed they’re taking this step to stop contraband from entering facilities, there’s little evidence these policies are working.)

Until the beginning of the 2010s, reporters who wanted to communicate with people who were incarcerated were restricted to phone calls, in-person visits, or mail. In the last decade, private telecommunications companies started distributing and selling personal tablets in incarceration facilities (and earning large profits by doing so). Most states and the federal prison system now have an electronic messaging system.

Typically, you must create an account on the electronic messaging platform used by the particular corrections facility or system, add the person you want to message to your list of contacts using their state-assigned ID number and then add money to your account.

Messages sent via systems like JPay may be delayed by days or even weeks before they reach their recipient. Since messages are monitored by corrections officials, some communications may be heavily redacted by the time they reach the person you contacted.

Also, many incarcerated people do not have personal tablets and so must view messages via a centralized kiosk, limiting access to communications. (This was often a problem during the early pandemic, as persistent lockdowns hindered access to kiosks where people could respond to messages.).

Like electronic messages, phone calls with incarcerated people are monitored by the corrections agency and can be costly to them. Unlike with electronic messages, you will not be able to contact incarcerated people. Instead, they will have to call you. Even if you have agreed to talk at a certain time, they may be delayed in contacting you, as lockdowns, long phone lines, or other problems may impede phone access.

You should assume that phone calls, messages sent through electronic systems, and regular mail are being read and monitored.

Incarcerated people do not earn a living wage, and the meager amount of money they may make from a job inside does not cover the cost of communicating with family members and friends, let alone journalists.

Both phone calls and messages on electronic systems can be exorbitant for them. In Alabama, for example, a 15-minute in-state call will run over $3.75. Like phone calls, electronic “stamps” that allow messaging range in price across states. A pack of 10 stamps costs $1.50 in New York and $4.40 in Florida.

So they may not be able to afford the cost of contacting you and could ask to place collect calls, or for you to send stamps so they can respond to your messages. It is typical for reporters who cover the criminal legal system to pay for a return stamp when contacting an incarcerated source and foot the bill for communicating with sources.

Although two main communications systems are used across most prison systems in the U.S., you will need to add separate funds for each state correction system (i.e., Florida stamps cannot be used to message people in New York prisons.).

In Arkansas, Georgia, Michigan, and Texas, correspondence with the news media is considered to be “privileged communication,” according to the Prison Policy Initiative. This designation means that prison staff can’t open and read the letters like they can with other correspondence. Even if you have this protection, at any point in your reporting process, your source may lose their ability to communicate with you.

Partnering to find additional sources

In some cases, you may have a good tip for an article but no incarcerated sources to help move the story forward. Cold-messaging incarcerated people isn’t guaranteed to get you any reliable information, and it could endanger the safety of the people you contact. In these cases, you may be able to find helpful sources through local organizations.

Public defenders or other legal advocacy groups will likely know if there are incarcerated people who are willing to speak for your story and might be able to facilitate communication. Activist groups will also often have information and incarcerated contacts who can assist with sourcing.

In some cases, activists may agree to organize a three-way phone call. This can both protect the incarcerated source from being identified (if they have asked to be anonymous) and speed up the process of getting in touch, as these activists will already be entered in the corrections agency’s communications system.

Many family members are part of Facebook groups focused on their particular state’s incarceration facilities or the place their loved one is imprisoned. They can direct you to useful sources at the facility who might provide critical insights.

In other cases, incarcerated writers can help, as they have a wealth of knowledge about their institution and the broader incarceration system that detains them. In recent years, grassroots organizations like Empowerment Avenue have helped incarcerated journalists get their work published in outlets like The New York Times, The Appeal, and The Marshall Project. Reading the work of these writers, which can also be found at websites like Prison Writers and the Prison Journalism Project, can provide insights about how to approach a story.

Due to the restrictions placed on incarcerated journalists — such as departments attempting to limit what work they can publish, censored communications with news outlets, and retaliation for writing negative stories — these writers may have information they chose not to publish. If you are building on the work of an incarcerated writer, you should offer them the chance to collaborate on a publication, co-report the story, and get paid for their contributions to the writing process.

Resources/Guides

- Scalawag Magazine/Empowerment Avenue’s America’s “The Press in Prison”

- “What Words We Use — and Avoid — When Covering People and Incarceration” from The Marshall Project

- Free Poynter training on covering jails and the language we use

- “Locked Up and Dying” series from CalMatters

- “Idaho jails withheld details about dozens of detainee deaths” from InvestigateWest

- “Locked In, Priced Out: How Prison Commissary Price-Gouging Preys on the Incarcerated” from The Appeal

- “They Were Wrongfully Convicted. Now They’re Denied Compensation Despite Michigan Law” from ProPublica