A legal loophole that lets the government buy location information, browsing history, and more from data brokers creates risks for journalists and whistleblowers.

Update on July 13, 2023: The National Defense Authorization Act amendment introduced by Reps. Warren Davidson and Sara Jacobs has been revised. Under the revised language, the amendment would prohibit only the Department of Defense from buying information it would otherwise need a warrant or other legal process to access. While this is a good start, Congress must close the data broker loophole for all intelligence agencies and state and local law enforcement.

A recently declassified government report revealing that federal intelligence agencies are gobbling up massive amounts of data from shadowy companies known as data brokers should raise alarm bells for all Americans, and particularly journalists and whistleblowers. Congress can — and should — close this data broker loophole using either the must-pass defense bill currently under consideration or separate legislation.

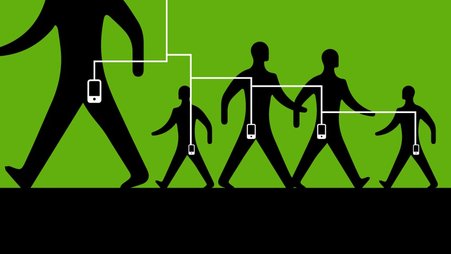

Unless you’re entirely off the grid, chances are good that a data broker has collected and sold highly personal information about you. Data brokers swallow up and compile data from online sources like search engines, social media, dating and weather apps, and more. They use that data to sell information about people’s religious or political beliefs, medical issues, sexual orientation, and even detailed location records. Despite claims that data brokers anonymize data, there’s plenty of evidence that it can often be traced back to specific individuals.

Data brokers’ invasive practices are creepy enough when they’re being used to sell stuff. But it gets worse. For years, intelligence and law enforcement agencies have been using data brokers as a loophole to get around the warrant requirement and other legal restrictions on accessing information for their investigations. And it’s not just the federal government relying on data brokers; state and local law enforcement use them, too.

This loophole is particularly dangerous for journalists and whistleblowers caught up in government leaks investigations. The government may be able to buy data about journalists and whistleblowers from data brokers that they couldn’t otherwise obtain without a warrant under the Fourth Amendment. And it’s not clear whether the Department of Justice’s news media guidelines, which limit compelled disclosure of newsgathering records from journalists by the DOJ, would apply to purchases of the same data from data brokers.

The government could, for example, buy browsing history from a data broker to discover what news sites a suspected whistleblower has visited or what searches they’ve conducted. This could reveal evidence of the whistleblower’s contact with journalists or intention to share information with the public.

The government could also attempt to ferret out a reporter’s source by buying location data of the journalist and of suspected sources to glean where they’ve been and whether they’ve met in person. In 2009, for example, when the government suspected a State Department employee of leaking to reporter James Rosen, it used security badge access records to show Rosen’s comings and goings from the State Department.

We shouldn’t let the government buy its way out of respecting the Fourth Amendment. Thankfully, at least some members of Congress agree. Reps. Warren Davidson and Sara Jacobs have introduced an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act that would prohibit the government from buying information that they’d otherwise have to get a warrant or other legal process to access. Similar bipartisan legislation, the Fourth Amendment is Not for Sale Act, was introduced by Sen. Ron Wyden in the last Congress.

Congress must close the data broker loophole and make clear that intelligence and law enforcement officials have to follow the law before they can access sensitive information about journalists and other Americans. When Washington Post reporter Bob Woodward met Deep Throat in an underground garage outside Washington, DC, to talk about what would become Watergate, they didn’t have to worry about a cellphone in their pockets, browsing histories, or internet searches leaving a trail of breadcrumbs for leaks investigators to follow. Journalists in the digital age must be more wary, but they should still get all the protections afforded by the Fourth Amendment.