The American experiment is premised on the idea that an informed public is central to self-governance and a functioning democracy. But today, that fundamental idea is being challenged, at times by the very people – journalists and the media – who should be its staunchest defenders.

In a new post, NYU journalism professor Jay Rosen traces how the debate over Snowden and the National Security Agency has sparked what amounts to a de facto effort to “repeal the concept of an informed public.” This is a critical point, and I want to draw a few more threads into the debate.

“My sole motive,” Edward Snowden told the Guardian in his first public interview, “is to inform the public as to that which is done in their name and that which is done against them.” Rosen describes Snowden as “the return of the repressed.” He writes: “By going AWOL and leaking documents that show what the NSA is up to, he forced Congress to ask itself: did we really consent to that? With his disclosures the principle of an informed public roared back to life.”

However, since that moment, there has been a profound effort by politicians and even some journalists to close down that debate. This opposition has taken many forms. Journalists and politicians have attacked Glenn Greenwald and tried to undercut the legitimacy of the Guardian. They have tried to write off NSA programs as balanced and well within the law. And most of all they have used fear and the threat of possible terror attacks to argue that any real debate about the details of America’s surveillance programs is simply a “discussion the public cannot afford to have.”

The question no one seems to be asking is what are the costs of not having that discussion – and can we afford those costs? When James Madison argued in 1822 that “A popular Government, without popular information, or the means of acquiring it, is but a Prologue to a Farce or a Tragedy; or, perhaps both,” it was a warning, but it was also a choice. In the face of nearly daily revelations about the state of security and surveillance in the US it is easy to feel overwhelmed, to toss our hands up and assume the decisions being made in our name are in our interest. But inaction is also choice. The second part of Madison’s quote, “A people who mean to be their own Governors, must arm themselves with the power which knowledge gives,” reminds us that too often information doesn’t want to be free, we need to demand it.

Right now, the administration continues to argue they welcome this debate. But New York Times reporter James Risen pointed out the hypocrisy of this position this week when he said on CNN, “In Washington these days […] people want to have debates on television and elsewhere, but then you want to throw the people who start the debates in jail.” He should know, because right now the Justice Department is trying to force him to reveal his sources in a different national security leak case. If he doesn’t, he’ll be thrown in jail.

In 2009, concern over the changes in media and journalism sparked a landmark report from the Knight Commission on the threats and opportunities to fostering an informed public. In their opening pages the authors of the report assert that “Information is as vital to the healthy functioning of communities as clean air, safe streets, good schools and public health,” and “if there is no access to information, there is a denial to citizens of an element required for participation in the life of the community.” The authors challenged America and its media to:

- Maximize the availability of relevant and credible information to all Americans and their communities;

- Strengthen the capacity of individuals to engage with information; and

- Promote individual engagement with information and the public life of the community.

The Knight Commission said that their vision was driven by the “critical democratic values of openness, inclusion, participation, empowerment, and the common pursuit of truth and the public interest.” Today, the challenge the Knight Commission set forth remains a useful guide as we look at the debates we face about the NSA’s spying programs and the associated revelations that have spun out from these disclosures.

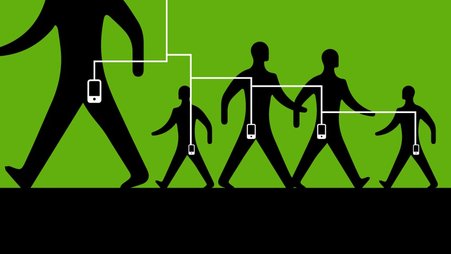

For too long, we’ve watched as government secrecy has escalated and made it more and more difficult for the public to be informed on critical issues from war and surveillance to the environment and the economy. Now we face a system so entrenched in secrecy that classifying documents is the norm in DC, the Justice Department feels empowered to monitor the phone records of journalists, states are passing Ag-Gag laws to curtail reporting and whistleblowing, and members of Congress are bold enough to suggest journalists be prosecuted for reporting the news of the day.

Mathew Ingram has even argued that “the worst part about all the government surveillance isn’t the snooping, it’s the secrecy.” For Rosen, this secrecy forces a central question about our relationship to our government and to each other:

“Can there even be an informed public and consent-of-the-governed for decisions about electronic surveillance, or have we put those principles aside so that the state can have its freedom to maneuver?”

The end result of the secrecy and the government’s almost frantic efforts to protect it, is a fundamental loss of trust. That lack of trust, in our government and by extension in each other, undermines every one of the critical democratic values Knight outlined above.

In her powerful book Talking to Strangers, which predates the NSA controversy by almost ten years, scholar Danielle S. Allen argues:

“As for distrust of one’s fellow citizens, when this pervades democratic relations, it paralyzes democracy; it means that citizens no longer think it sensible, or feel secure enough, to place their fates in the hands of democratic strangers. [...] Within democracies, such congealed distrust indicates political failure. At its best, democracy is full of contention and fluid disagreement but free of settled patterns of mutual disdain. Democracy depends on trustful talk among strangers and, properly conducted, should dissolve any divisions that block it.”

For Allen, and for the Knight Commission, our security and our democracy is based on trust and openness. That’s why the NSA programs aren’t just a threat to the Fourth Amendment, but also the First Amendment by violating people’s right of association and chilling speech. “People who make a career in journalism cannot pretend to neutrality on a matter like that,” Rosen concludes. “If a free society needs them — and I think it does — it needs them to stand strongly against the eclipse of informed consent.”

I couldn’t agree more.