It was great to read this Edward Snowden New York Times op-ed—great because the piece is as thoughtful and informative as you’d expect, and even better because it’s an example of Snowden’s continuing ability to raise awareness of the dangers of an unchecked surveillance state. In fact, Snowden has been notably public of late, giving interviews, addressing huge crowds, receiving awards, and otherwise adding to and amplifying the worldwide discussion he catalyzed with his revelations of two years ago (this short video gives an idea of how many people Snowden has been reaching).

It’s interesting to see just how much the US government and its authoritarian backers hate Snowden’s ability to continue to contribute to the mass-surveillance debate. Prosecutors are actually trying to persuade judges to prohibit Snowden’s name being uttered in court (a tactic Snowden’s lawyer, Ben Wizner of the ACLU, aptly tweeted as He Who Must Not Be Named). Former Bush 2 White House Press Secretary and Fox News personality Dana Perino, apparently not realizing her Fox colleagues have themselves been trying to land a Snowden interview, protested that “The New York Times op-ed page gives valuable space to a traitor,” and Council on Foreign Relations war enthusiast Max Boot issued a similar complaint (the Boot piece also stands out as a masterpiece of psychological projection). As Jason Leopold has revealed, various lawmakers begged the Defense Intelligence Agency for classified dirt they could use to discredit Snowden. And the government’s use of the Espionage Act, which whistleblower attorney Jesselyn Radack explains has morphed into a strict liability law that precludes defendants from explaining their actions, is itself a deliberate attempt to silence the voices of Snowden and whistleblowers like him.

Even by the standards of an age where a new mass-surveillance law is named The Freedom Act (admittedly, something of an improvement on its mass-surveillance progenitor, The Patriot Act, but still), there’s a lot of Orwell at work here. Protests about Snowden having a public forum are really complaints about Thoughtcrime. Lawmakers trying to smear Snowden are hoping to turn him into Emmanuel Goldstein. The government’s efforts to prohibit even the utterance of Snowden’s name in court, and its use of the Espionage Act itself, are attempts to render Snowden an unperson.

Of course, the entire “if you have nothing to hide, you have nothing to fear” rubric is itself an internalization of the dangers of Ownlife, a.k.a. privacy. Snowden himself nailed the vapidity of this reasoning, noting that “Arguing that you don’t care about the right to privacy because you have nothing to hide is no different than saying you don’t care about free speech because you have nothing to say.”

And could there be a better example of doublethink than attempting to argue—after various court actions declaring NSA bulk surveillance to be illegal and unconstitutional, after Congress has finally reined in at least some NSA excesses via the “Freedom Act”—that Snowden should be punished for revealing the programs in question? For a recent example of the “revelations good; revealing them ungood” neurosis in action, here’s an LA Times op-ed with the doublethink right in the title: Snowden Deserves Credit for NSA Reform—and to Stand Trial (don’t miss Glenn Greenwald’s evisceration of the op-ed and the mentality behind it). And here’s an excellent analysis of the phenomenon by Jay Rosen—The Toobin Principle, named after CNN’s Jeffrey Toobin, whose attempts to praise the revelations while vilifying the man have led to contortions a seasoned yogi might envy.

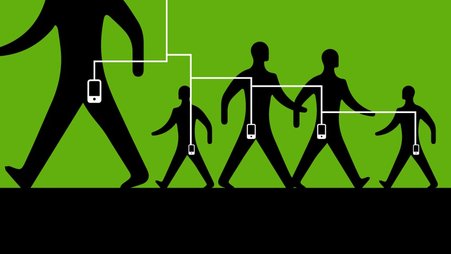

If I were an oligarch, I wouldn’t be pleased about any of these Orwellian tactics. I’d be worried. Because trying to suppress someone’s ability to speak—trying to suppress even the mention of his name—isn’t a sign of strength. It’s a sign of brittleness. And while the telescreens in Nineteen-Eighty-Four monitored only in one direction, thanks to Snowden, we’re finally beginning to monitor back.

Barry Eisler is a best-selling thriller author who spent three years in a covert position at the CIA Directorate of Operations. You can read more about his work at his website.