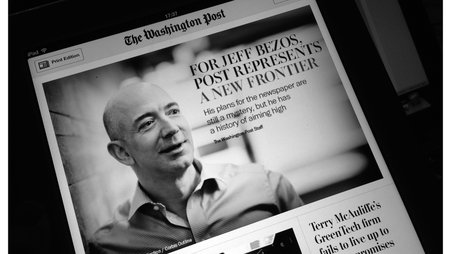

The prosecution of a former government official accused of murdering reporter Jeff German, pictured here, has sparked a legal battle that threatens to erode Nevada’s reporter’s shield law.

The tragic murder of Las Vegas Review-Journal reporter Jeff German — allegedly committed by a county official whom German was investigating — was already a nightmare scenario for those who care about protecting journalists and the free press. Now, a legal battle over demands to search German’s phone and other devices threatens to exacerbate the harm to press freedom by weakening Nevada’s reporter’s shield law, currently considered one of the strongest in the country.

We’ve written before about prosecutors’ efforts to search German’s devices and the Review-Journal’s objection. The newspaper has argued that the search could reveal German’s confidential sources — including for the very reporting over which he may have been murdered — and that the First Amendment and Nevada shield law forbid it. Unfortunately, the district court judge has been sympathetic to the prosecution, drafting an order that would allow two police detectives and two prosecutors to search the devices.

Thankfully, the district court doesn’t have the final say. The Review-Journal has appealed to the Nevada Supreme Court. More than 50 press freedom and media organizations, led by the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press and joined by Freedom of the Press Foundation (FPF), filed an amicus brief in support of the newspaper, pointing out that the state Supreme Court’s decision could impact all Nevada journalists and the public’s access to newsworthy information.

The whole purpose of the Nevada shield law is to encourage the free flow of information to the public by assuring sources that reporters can’t be forced to violate promises of confidentiality. There’s nothing in the law that says a reporter’s death ends the privilege. That makes sense, since a reporter’s death doesn’t lessen the risk to a confidential source whose identity is divulged.

It would be perverse to allow prosecutors and police to weaken a key protection for journalists and their sources in the name of prosecuting a man accused of murdering a reporter. The district court’s ruling was also completely unnecessary. The Review-Journal had offered to waive its privilege if independent special masters were appointed to review the data from the devices, to first determine whether the data is even covered by search warrants that have been issued. (On appeal, the newspaper is asking the Nevada Supreme Court to hold that the devices can’t be searched at all. But, if the court doesn’t make that ruling, it asks the court to apply this protocol.)

The district court, however, rejected this reasonable request. Instead, it prefers to allow searches by the very police and prosecutors whose colleagues may have been confidential sources for German over the years. The district court may believe that its confidentiality order guarantees there won’t be any leaks of source names within law enforcement or the district attorney’s office. However, that’s unlikely to reassure sources who may have risked their careers and personal relationships to speak to German and who entrusted him, not cops and prosecutors, to keep their identities secret.

If the Nevada Supreme Court doesn’t rule for the Review-Journal, it won’t be just German’s sources that are at risk. All confidential sources in Nevada will have to think twice before speaking to a reporter if they know the reporter’s death makes her promise of confidentiality meaningless. That’s bad for reporters, sources, and the public. If Nevada’s shield law, which has been in place for half a century, is to remain robust, the Nevada Supreme Court must bar the search of German’s devices.