When federal agents raided Washington Post reporter Hannah Natanson’s home earlier this month, it reignited discussions about how reporters can protect confidential sources and sensitive information.

“Having reported from dozens of countries with various levels of surveillance, I’ve found that the safest method for interacting with sources who would face the most jeopardy if exposed is to meet in person and cover your tracks,” said Steve Herman, executive director of the Jordan Center for Journalism Advocacy and Innovation, in a recent statement by the National Press Club Journalism Institute.

That’s good advice. But “covering your tracks” when meeting sources isn’t always easy. And a new Supreme Court case, Chatrie v. United States, could make it harder.

The dangers of geofence warrants

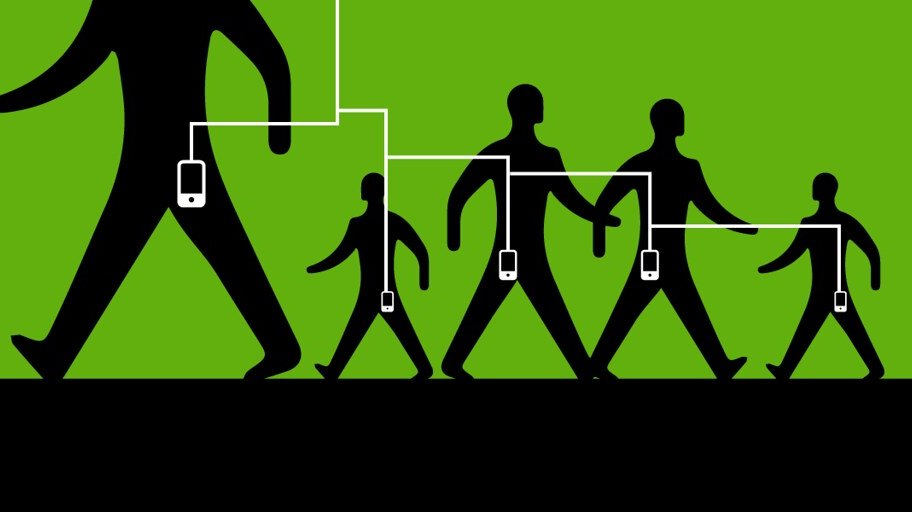

At the heart of the Chatrie case are legal orders known as geofence warrants. This controversial tool allows police to demand location data from tech companies (usually Google) to see every device in a specific area at a specific time. Imagine drawing a digital fence around a crime scene and demanding a list of every phone that crossed into it.

These demands can reveal precise details about people’s movements and locations. Authorities can pinpoint where someone stood within a couple of yards and whether they were on the first or second floor of a building.

But geofence warrants are also imprecise: They sweep up the movements not just of suspects but also of innocent people who happen to be within the digital fence. Demanding location data for a 150-yard radius of a bank in the hour before it was robbed, for example, may show the movements of people who worked at the bank, visited the psychiatrist’s office next door, worshipped at the church on the neighboring block, or dropped into the nearby strip club.

Lower courts disagree about whether these demands violate the Fourth Amendment’s protection against unreasonable searches and seizures. Some have held that they’re categorically unconstitutional. Others, like the appeals court that made the initial decision in Chatrie, have held that geofences are not a “search” under the Fourth Amendment and would be perfectly constitutional even without a warrant.

Now, the Supreme Court will decide. If the court holds that the Fourth Amendment’s warrant requirement does not apply to the use of geofences to obtain location data, it could greenlight mass surveillance on an enormous scale. The government could require tech companies to turn over location data, enabling it to surveil protesters, members of dissenting groups, and even the press.

A direct threat to journalists and sources

For journalists, the threat of their location data landing in the government’s hands is real. As our digital security training team at Freedom of the Press Foundation (FPF) explains:

“Consider a sensitive story in which you are meeting a high-risk, anonymous source in person. Your adversaries could use location data to determine that you and the source were in the same spot at the same time, leading to the possible exposure of the source’s identity.

“Or perhaps you need to visit a particular location (e.g., a government building) that could put a given department or agency on notice that you are investigating them, in turn making the reporting process more challenging.”

Geofence warrants could easily expose confidential sources or tip off powerful government institutions that a reporter is investigating them. A single geofence warrant centered on a newsroom, for instance, could reveal everyone who’s visited, from whistleblowers to workers.

Even reporters who take precautions, like meeting sources in neutral locations, might not be safe. A geofence warrant could place them within yards of each other in the same parking garage or cafe, revealing their connection.

Holding that the Fourth Amendment applies to geofence warrants would prevent some of these abuses. Under the Fourth Amendment, courts must only approve warrants if there’s probable cause, which is unlikely to exist in fishing expeditions targeting journalists to uncover their confidential sources.

Why this matters, even after Google’s changes

Google took an important step in 2023 by changing how it stores user location data and for how long, making it harder for the government to use geofence warrants. But these protections aren’t foolproof. Other location data collected by Google or other companies could be vulnerable to geofence warrants.

As a result, the court’s decision in Chatrie still matters, and journalists may still want to take steps to limit exposure of their location data.

The outcome of Chatrie also touches on a deeper Fourth Amendment issue that could reverberate beyond geofence warrants: the “third-party doctrine.” This decades-old legal rule says that people lose their reasonable expectation of privacy once they share information voluntarily with third parties, like a phone company or a bank.

The court has limited the third-party doctrine in recent years, most famously in its decision in Carpenter v. United States. But its ruling in Chatrie has the potential to swing the pendulum back toward less privacy. That could impact Fourth Amendment protections for all kinds of data shared with third parties, such as information stored in the cloud or sensitive searches.

Every journalist, source, and citizen should be paying attention and demanding greater privacy protections from the courts and from Congress. If privacy is restricted in this case, our First Amendment rights are too. The free press can’t exist in a surveillance state.