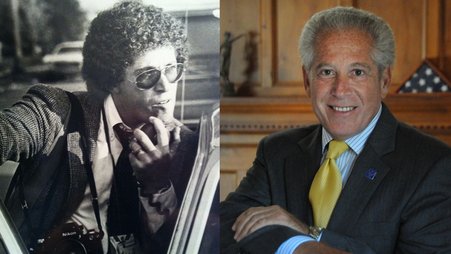

Long before he was the Freedom of Information Act director at The Washington Post, Nate Jones was a curious college student with a penchant for Able Archer 83.

Looking to learn more about the 1983 NATO war game, he ventured to the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and sifted through a box inscribed “military exercises.” The folders inside were empty and classified.

“You can do FOIA, but good luck,” an archivist told him. “So instead of giving up, I kind of got a little angry,” he recalled.

Jones funneled that FOIA frustration into fanaticism. Years later, he acquired the documents his college self had yearned for and eventually wrote a book about the war scenario based on them.

But the lesson he learned transcended Able Archer 83. Access to even one unclassified document from the jump is all it would have taken to start a chain reaction of declassification for Jones much sooner.

“If the dang Reagan Library had just given me the records right away, it would have helped me file tens of thousands of more public records requests,” he explained.

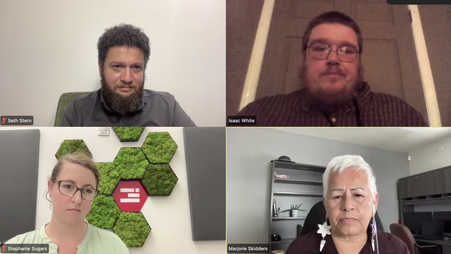

To understand how FOIA requests and public records like those ultimately obtained by Jones can be used to fight government secrecy and improve our communities, Freedom of the Press Foundation (FPF) hosted an online webinar June 24 with Jones, MuckRock CEO Michael Morisy, and investigative journalist and author Miranda Spivack.

Morisy, whose organization has helped file over 156,000 records requests and led to the release of over 11 million pages, said the key to a successful FOIA lies in its preparation. As a starting point, he advises requesters to “step inside the mindset of a bureaucrat” and envision the request from their perspective.

“Where are the records that you care about? How would you describe them? How would they work? Who would have access to them? And then use that to guide that public records officer to exactly what you want,” he said.

Spivack — who recently authored “Backroom Deals in Our Backyards: How Government Secrecy Harms Our Communities and the Local Heroes Fighting Back” — said it’s also important to consider the system of records requests as a whole, beyond the individuals working within them.

Unlike at the federal level, she said, there isn’t a constituency for transparency at the state and local levels “until somebody bumps into a problem.” That can stifle requesters.

“There are a lot of groups at the state and local level that are pro transparency, but I think they really have to get into communities and have to translate for people why it matters,” added Spivack. “Not even when you need it, but before you need it, why it should matter that your government should be more transparent.”

Still, there are cases where a local or state government records office can provide more information than a federal one, which is why Spivack recommends filing requests with both parties when it’s appropriate to do so.

Jones concurred. “It’s a great strategy to always file with as many agencies as you can.”

Another helpful strategy is to replicate prior successful records requests, he said.

“Don’t reinvent the wheel. Have an agency release more of what they already have released,” Jones said. Many reporters, including those at the Post, use MuckRock to find examples of past successful requests and duplicate them to save time and increase their odds of a successful request, he added.

As the Trump administration slashes FOIA offices and prunes the National Archives and Records Administration’s budget, one audience question, from open government advocate Alex Howard, addressed the possibility of insulating FOIA offices from political influence and firings.

Jones suggests modeling FOIA offices more closely on the Inspector General’s Office, which could add pressure on people in the agency “to release the things to the public in a timely manner.”

“So if you want to call it insulation, that would be fine, but I would rather call it empowerment,” he added.

Looking ahead, Morisy said that the encroachment of corporate interests in records requests is contributing to the “hollowing out” of government competence and could be clogging up the system. Instead of fighting together, transparency constituencies are picking individual battles, he said, which waters down their ability to enact change within the system.

“I think they’re losing, which I think is a big, big problem,” Morisy said.

Still, Jones is optimistic about the system, even if it’s far from perfect. He encourages requesters to file weekly, if not daily, to open the tap on a consistent flow of releases. Following that ethos could yield “one or two or three good documents a week,” he said.

“Be a proactive requester, not a reactive requester,” Jones said. “If you plant your acorns, the trees will grow.”