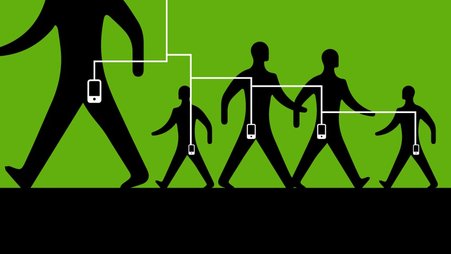

A secret surveillance program that allows law enforcement agencies to monitor trillions of phone records without a warrant could be used to target journalists and sources. Woman talking on her mobile phone on outdoor by wuestenigel is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

A secret U.S. surveillance program revealed by Wired last week allows federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies to monitor trillions of phone records of Americans without a warrant. It’s a chilling reminder that Congress must take steps to rein in government spying powers. But instead, it is slow-walking reform. Indeed, some lawmakers are currently considering simply reauthorizing a controversial law that’s been abused to surveil Americans, including journalists.

The Wired report discusses Data Analytical Services, previously known as Hemisphere. With the cooperation of AT&T, DAS lets law enforcement agencies obtain phone records of both a specific target and of everyone they’ve communicated with. That means that even someone never suspected of a crime could be monitored.

DAS data can reveal highly sensitive and personal information, including names and addresses of subscribers, phone numbers, and the dates, times, durations, and locations of the calls. All of this can reveal callers’ location information and associations. For example, DAS data could be used to determine whether someone has spoken to a journalist on the phone, for how long, and on what dates, as well as the same information for everyone else that journalist has spoken to. (DAS data does not reveal the contents of communications.)

DAS is ostensibly aimed at drug trafficking, but journalists reporting on the drug trade — and their sources — shouldn’t be surveilled without a warrant. In addition, DAS isn’t limited to drug crimes. Law enforcement agencies can search the data for any reason, and police have requested DAS data for cases unrelated to drugs in the past.

It doesn’t take a huge leap to imagine that a power-hungry local police department determined to “investigate” journalists for newsgathering on a wide variety of topics could request DAS data to reveal reporters’ sources.

Other loopholes need to be closed

Wired’s reporting on DAS should be a wake-up call to every member of Congress that they need to put up guardrails to limit the government’s spying powers. But DAS isn’t the only massive loophole that allows the government to conduct mass warrantless surveillance on Americans.

We’ve written before about how Section 702 of the Foreign Surveillance Intelligence Act, or FISA, allows intelligence agencies to conduct “backdoor searches” to access the communications of Americans (including journalists) without a warrant, as long as they’re talking to someone outside the U.S. The sunset of Section 702 at the end of the year is a prime opportunity to end warrantless surveillance of Americans’ communications.

In addition, Congress must end other government spying powers like the “data broker loophole,” which lets law enforcement agencies simply buy data that they would otherwise need a warrant to obtain.

Surveillance reform bill on the table

The Government Surveillance Reform Act — a bill sponsored by Sens. Ron Wyden and Mike Lee and Reps. Warren Davidson and Zoe Lofgren — would address these concerns. Among other things, it would prohibit backdoor searches of Americans’ communications in criminal investigations without a warrant, with a few limited exceptions, and close the data broker loophole.

Instead, the Biden administration is pushing Congress to reauthorize Section 702 without significant reforms. FBI Director Christopher Wray has claimed that internal controls have increased agents’ compliance with the law, making legislative reforms unnecessary.

Yet it would be a mistake to reauthorize Section 702 without significant restrictions. The government has demonstrated that it can’t be trusted to police its own surveillance powers. Even after the internal controls touted by Wray were put into place, the FBI’s own audit found that there were 8,000 warrantless FBI searches last year that were out of compliance with FISA.

To buy themselves more time, some lawmakers are considering adding a short-term reauthorization of Section 702 to the National Defense Authorization Act, which Congress must pass by the end of the year. This, too, would be a mistake. To ram Section 702 reauthorization through Congress with the NDAA is unnecessary and risks encouraging further extensions of the law, as a coalition of civil society organizations including Freedom of the Press Foundation (FPF) have warned.

Congress shouldn’t need more evidence that government surveillance needs to be restricted, nor any more time to gather it. Congress must act now to reform Section 702 and close other surveillance loopholes to protect the civil liberties and privacy of millions of Americans — including journalists and their sources.