This week, Congress held its first hearing on the Freedom of Information Act in three years, and it was the first to feature public witnesses since 2015.

In fact, the Senate Judiciary Committee hearing didn’t hear from any federal employees at all — in large part because the Trump administration recently fired the most likely government witnesses.

The timing of the hearing raised questions about whether Congress can defend FOIA offices from the administration’s mass firings, as well as about the future of a law that has enjoyed bipartisan support for 60 years.

Targeting FOIA officers?

Sen. Chuck Grassley, the Republican committee chair, began the hearing with a call for bipartisanship.

Quoting former Democratic Sen. Russell B. Long, Grassley said government secrecy “dampens the fervor of its citizens and mocks their loyalty.”

He went on to cite long-standing problems with FOIA administration, from backlogs and delays to the growing need for requesters to file lawsuits because their original requests were ignored or denied.

These are the same problems that have been raised at every FOIA hearing in recent memory — but solutions have proven elusive, and congressional frustration that agencies are unwilling or unable to faithfully implement FOIA was apparent throughout the hearing.

One senator (John Kennedy of Louisiana) suggested that FOIA officers should be held personally liable for willfully withholding information.

This is not a new idea, but is it a good one?

When withholding information, most FOIA officers are either following the agency’s standard operating procedures, relying on the nonnegotiable advice of agency counsel, or they are trying not to lose their job by embarrassing a political appointee who is several levels above them.

Putting a target on the back of individuals working in FOIA offices that are stymied by systemic problems may only serve to discourage federal employees from pursuing FOIA as a career path in the first place, and worsen a growing shortage of qualified information professionals.

Glaring absence of FOIA officials

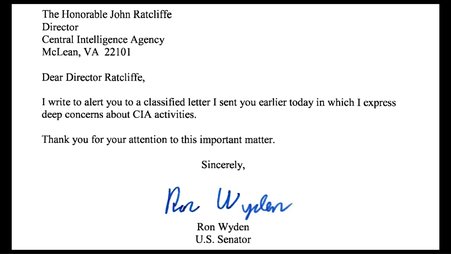

This gets us to one of the biggest problems overshadowing this week’s hearing: The committee was only hearing from members of the public because many FOIA officials have been fired by the Trump administration.

The hearing’s most glaring absence was the director of the Justice Department’s Office of Information Policy, who is in charge of encouraging agency compliance with FOIA and whom the Trump administration fired a month ago.

Also looming over the hearing were reports that the entire FOIA office at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had been fired, as well as many other FOIA officers across the rest of the Department of Health and Human Services.

Despite the unique crisis FOIA offices are facing at this moment, most of the hearing stuck to less controversial topics than the Trump administration’s staffing decisions, and focused instead on how agencies could better incorporate artificial intelligence and machine learning into FOIA search and review. (An obvious solution is that Congress could explicitly fund such an endeavor, although this was not mentioned in the hearing.)

There’s nothing wrong with the administration initiating its own declassification projects, but it should not be the only way for the public to see government records.

The big picture — public’s right to know at risk

At the same time that agency FOIA offices are being gutted, the broader information environment is becoming increasingly dominated by one perspective: that of the White House.

The Trump administration has been adamant that transparency and declassification are priorities this term. It is promoting selective declassification efforts like the JFK assassination records and records on the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic (albeit only from certain intelligence agencies; health agencies have been muzzled).

There’s nothing wrong with the administration initiating its own declassification projects, but it should not be the only way for the public to see government records.

And the risks are high of only declassifying what the White House wants, especially when inconvenient information is being deleted from agency websites, free access to information through public libraries is under threat, museums are facing pressure to whitewash their exhibits, and FOIA offices are being decimated.

This places renewed emphasis on Congress to step up the urgency of its FOIA oversight.

If it waits another three years to hold a FOIA hearing, much less pass legislation that includes dedicated funding and staffing levels for FOIA offices, how many FOIA officers will be left to try and ensure the public’s right to know?