Dear Friend of Press Freedom,

What will Donald Trump’s second term mean for government secrecy?

I’m Lauren Harper, the first Daniel Ellsberg Chair on Government Secrecy at Freedom of the Press Foundation (FPF). If you’re concerned about what Trump’s second term might mean for transparency norms, access to government records, attempts at congressional oversight, and more, consider subscribing to “The Classifieds” — FPF’s weekly newsletter highlighting important secrecy news that shows how the public is harmed when the government keeps too many secrets.

To give you an idea of what’s to come, here are three secrecy issues that I’ll be following closely over the next four years.

All the president’s records

Trump showed a consistent disregard for preserving presidential records during his first term.

He ripped them up, he tried to flush them down the toilet, he didn’t create them when he should have, and his staff used disappearing messaging apps to prevent permanent preservation of White House correspondence.

But perhaps most famously, he refused to transfer rightful ownership of his presidential records to the National Archives and Records Administration at the end of his term, which has been required of every president and vice president since Jimmy Carter’s administration.

Worst of all, none of the legal actions against Trump since he left office attempted to enforce compliance with the Presidential Records Act. And Congress has as yet proven unwilling to strengthen the statute to prevent Trump from recklessly destroying presidential records.

Thwarting oversight

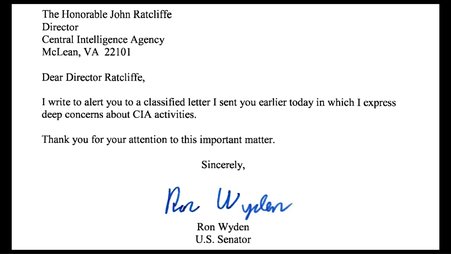

Government oversight happens in two important ways: through Congress and through agencies’ inspectors general. Trump tried to impede both during his first term.

The first Trump administration banned agencies from responding to congressional requests for information when those requests did not come from full committees or subcommittees. This stalled legitimate oversight being conducted by the minority.

If this happens again, it will be important for minority staff to train themselves on the rights of individual members to request information directly from agencies, and how best to counter agencies’ objections to providing information.

Trump also undermined the effectiveness of inspectors general across the government during his first term by either replacing them (IGs are nonpartisan and usually have open-ended appointments), firing them, or leaving those positions vacant.

There are currently 15 vacant IG positions across the government, so agencies like the CIA, NSA, and NASA do not have officials in place to conduct agency investigations.

How much worse can FOIA get?

Federal agencies are required to preserve their records in accordance with the Federal Records Act and the public is allowed to request access to those records under the Freedom of Information Act. But Trump undermined both laws by appointing agency heads who discouraged federal officials from creating records in the first place and who explicitly sought ways to avoid compliance with FOIA.

This trend will likely continue. FOIA backlogs will continue to grow, and requesters will be increasingly forced to sue if they want documents to see the light of day.

Of course, Trump didn’t break FOIA during his first term — it’s been in bad shape for a long time, and President Joe Biden didn’t make it any better.

But Biden’s inaction on improving FOIA means the public will have an even more difficult time accessing the records it needs to investigate abuses of power or understand public health threats under the second Trump administration.

Biden’s secrecy legacy

Biden didn’t just drop the ball on FOIA. He also didn’t issue a new executive order on classified national security information. The current one dates to the Obama administration and has two sizable problems. First, it does not explicitly prohibit agencies from classifying — and therefore hiding — information that documents violation of law. Second, it does not define the terms used to designate classification categories. This leads to too many subjective and unnecessary classification decisions.

He also did not use his authority to declassify records the public has expressed overwhelming interest in seeing, even when their release would promote a better understanding of government activities and would not damage national security. For example, he did not declassify the CIA torture report, and he did not declassify the remaining JFK assassination records.

Worse yet, Biden’s Justice Department continued to keep Office of Legal Counsel opinions secret, and the National Archives and Records Administration, which is supposed to ensure that the government’s most important records are preserved for the public, is still not receiving adequate funding.

The Biden administration does deserve real credit for appointing a director of national intelligence who acknowledges that the government’s approach to classifying information “is so flawed that it harms national security and diminishes public trust in government.” This helped Biden establish a formal declassification program that revealed information whose release helped achieve strategic national security goals.

But Biden’s missed transparency opportunities outweigh the good declassification intentions of a handful of senior officials.

Now, Trump will enter his second term emboldened in his belief that it’s OK to destroy records and bully agencies into keeping information from Congress and the public.

When that happens, FPF will be here to remind the White House what its responsibilities are, remind Congress what its authorities are, and remind agencies that their records belong to the public.

If you haven’t yet, subscribe to The Classifieds and FPF’s other newsletters for regular updates on all the news you need to know about secrecy, press freedom, digital security, and more.

Transparently yours,

Lauren Harper