Last summer, Shirley L. Smith, an independent investigative journalist from the U.S. Virgin Islands, reached out about her efforts to get lawmakers there to modernize the territory’s public records laws. Having reported from jurisdictions with better (although far from perfect) transparency systems in place, she was sick of getting the runaround, and realized that the archaic and toothless laws on the books made evasion of records requests possible.

Our response was something like, “Where have you been all our lives?” We’ve spent years imploring journalists to advocate for their own legal rights — whether by fighting for transparency, pushing for laws to protect journalist-source confidentiality, or speaking out against abuses of federal and local laws to target newsgathering. No matter what one thinks about the place of “objectivity” in contemporary journalism, it’s absurd to let it get in the way of standing up for reporters’ own rights.

Smith — who has previously worked for outlets including the now-defunct Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting, The Atlanta-Journal Constitution, The Telegraph in New Hampshire, and The Virgin Islands Daily News — told us she focuses on “long-form enterprise and investigative reporting on social justice issues and institutional inequities.” Her current work looks at “the impact of longstanding and often overlooked environmental hazards in the U.S. Virgin Islands and other issues that affect the welfare of residents.”

We spoke to Smith about her experiences reporting in the territory and why she decided to pursue reforms to its public records laws.

What obstacles are you encountering due to the local public records laws?

Between October 2022 and July 2025, I submitted public records requests to multiple government agencies in the U.S. Virgin Islands for records related to serious health, environmental, and safety issues that pose a risk to the community. Officials have ignored most of my requests. Those that did respond provided incomplete information after lengthy delays, or flimsy excuses — without legal justification — for why they could not release documents.

One of the most outrageous responses I received was from the police department. They said I have to provide proof of “Virgin Islands citizenship” to access public records, and they refused to send me copies of any records. Instead, they insisted I come into the police station to examine records.

A huge part of the problem is that the Public Records Act is outdated and weak. It does not require agencies to respond to public records requests within a specific time frame, which allows for lengthy delays with impunity; the penalty for violating the law is only $100; and the only recourse one has if an agency violates the law is to file a lawsuit, which will cost more than the $100 penalty. Also, the law was enacted in 1921, before the advent of the internet and other technological advances that are commonly used to conduct business and law enforcement efforts, so the law needs to be updated to include electronic records.

You’ve reported from all over the country. What is uniquely challenging about reporting on the USVI?

The USVI is a small territory, consisting of three main islands — St. Thomas, St. Croix, and St. John — with a total population of approximately 87,000, according to the most recent census. Although there are three branches of government — executive, legislative and judicial — the territory has a somewhat centralized government that is difficult to penetrate, because the governor wields most of the power.

Shirley Smith“I only had two choices. I could capitulate or petition the USVI Legislature to revamp the territory’s archaic and ineffective public records law.”

The governor, who manages the affairs of the territory with some federal oversight, appoints the head of almost all government agencies, the members of agency boards, the attorney general, and the local judges. All appointments must be approved by the USVI Legislature, but these officials still serve at the pleasure of the governor.

Historically, the Democratic Party has been the predominant party in the territory, so most public officials, including the governor, are part of the Democratic machine, and most residents work for the government or are affiliated with someone who works for the government. Therefore, a lot of residents are intertwined with the government. As a result, many residents and public officials are either reluctant or fearful to speak to the media for fear of retribution from the administration. Since tourism is a major driver of the economy, some officials also try to downplay certain issues that may reflect poorly on the territory.

Additionally, the territory only has a handful of news outlets, and they do not have the resources to support in-depth investigative reporting, and the national media are usually not interested in issues in the USVI unless there is a major crisis. Hence, many issues are not covered or are underreported.

While the federal government monitors some activities in the territory, the Trump administration has rolled back certain environmental regulations and programs that were intended to protect residents’ health and safety. They have also made it difficult for the media, particularly independent journalists, to access certain federal records and data. This means that USVI residents cannot count on the kind of oversight they had in the past from the federal government to protect them. This is also extremely disturbing because usually, if journalists cannot obtain records from a local government, they can request the records from the relevant federal agency and vice versa. But now, it is difficult to get records related to the USVI from the local and federal government.

The confluence of all these factors impedes the media’s ability to hold public officials accountable, root out corruption, combat misinformation, and provide the public with accurate, untainted information. This can have devastating consequences in an emergency or crisis.

Why should journalists and news consumers in the mainland United States be concerned about public records laws in the USVI when there are so many attacks on press freedom and transparency coming from the federal level?

People born in the U.S. Virgin Islands and other U.S. territories, like our neighbors in Puerto Rico, are U.S. citizens. Yet, we are often treated as second-class citizens by the federal government. Under the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, journalists have the right to monitor the activities of the government on behalf of the public, and that includes the right to examine and get copies of public records. Recent events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and military actions in the Caribbean, have magnified the need for access to public records at every level of government, including U.S. territories, because what happens in the Caribbean can have a ripple effect throughout the country. Also, many national stories emerge from local incidents.

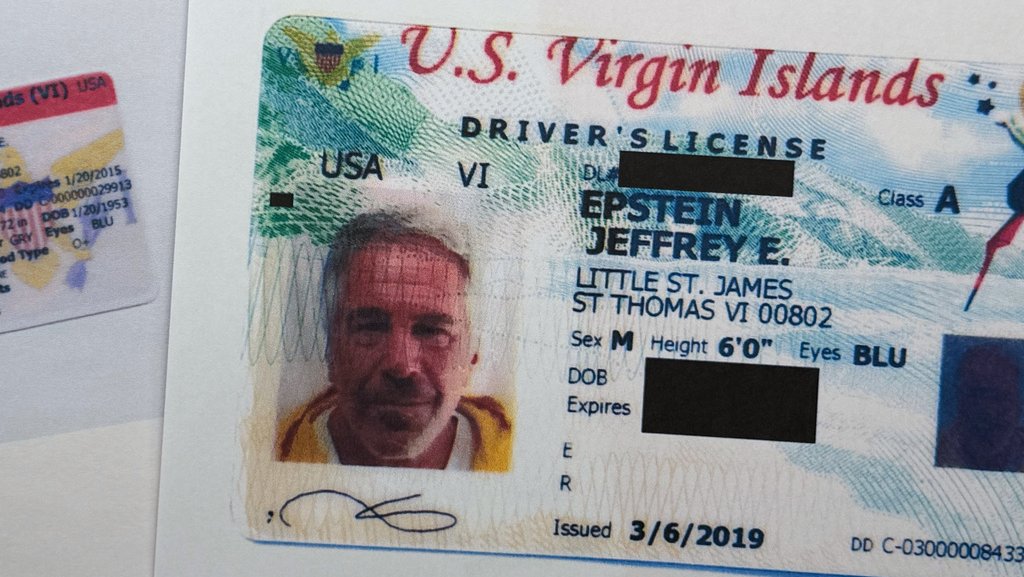

Another case in point is the Jeffrey Epstein case. The private islands formerly owned by Epstein, where he and other powerful men allegedly sexually abused underage girls and women, are located in the U.S. Virgin Islands. The Virgin Islands also receives a lot of federal funds, and American taxpayers have a right to know how this money is spent.

Journalists are often reluctant to go on offense in advocating for their rights to gather news. They might take the government to court over a denial of a specific records request, but they’re less inclined to try to change the law more broadly. Talk about why you chose to go down this path.

As an independent journalist, I do not have the resources to file a lawsuit, and I could not find an attorney or a media advocacy organization to assist me with obtaining the records I requested. So, I wrote an op-ed about the government’s lack of transparency and my personal experience, but I realized that writing an article was not enough to ensure lasting change and accountability. Therefore, I only had two choices. I could capitulate or petition the USVI Legislature to revamp the territory’s archaic and ineffective public records law.

As a journalist, I had some trepidation about petitioning the legislature because I did not want to be viewed as a biased advocate or a lobbyist. But extraordinary circumstances require extraordinary actions. And, I don’t think journalists should shy away from the term “advocate” anymore. Journalists should be advocates for the truth, justice, and accountability for the public good. This initiative is about preserving journalists’ constitutional rights to seek the truth and monitor the government, so we can hold those in power accountable and provide unbiased, accurate news coverage to the public, so they can make informed decisions.

Shirley Smith“What happens in the Caribbean can have a ripple effect throughout the country...Many national stories emerge from local incidents.”

Journalists cannot afford to wait around for others to fight for us when there are blatant attempts by the government to silence and discredit us, control the news narrative with distorted facts, and when people’s health and safety and our own lives and livelihoods are increasingly at risk because every time those in power succeed in stifling the media — whether it be on the local, national or international level — it emboldens others to follow suit. This will eventually lead to a government-controlled media and the further dismantling of the fundamental principles of democracy that we are seeing play out across the nation.

It has been an exhausting battle, but I am no longer in this fight alone. The Freedom of the Press Foundation (FPF) and the VI Source, a local news outlet, have partnered with me in this initiative. Thanks to FPF’s efforts, I have also garnered the support of 11 other national advocacy organizations, including the Joseph L. Brechner Freedom of Information Project at the University of Florida College of Journalism and Communications. They submitted a joint letter of support for this initiative to the VI Legislature.

You’re doing this as an independent journalist without a big legal budget. Do you think it’s fair that someone in your position needs to take the lead on this or should bigger outlets, whether in the USVI or elsewhere, be stepping up?

It is definitely not fair, but necessary. Segments of the local media have successfully sued the government in the past, but they either do not have the resources to do so now or are unwilling to sue for whatever reason. Unfortunately, the plight of freelancers is often disregarded or overlooked in the journalism industry. Over the past two years, I reached out to several notable national media advocacy organizations, but I could not find anyone to assist me with obtaining public records.

The lack of access and stonewalling tactics by public officials, including the governor’s communications team, which removed me from their media list shortly after I asked the governor a question about a water crisis at a news conference, have hampered my ability to gather information that is critical to my investigation and report the news. But, as I indicated, this initiative to revamp the territory’s public records statute and strengthen its other sunshine laws is bigger than me. People have the right to know what is going on in their government — especially when it comes to their health, welfare and safety — not just what government officials want them to know to promote their agenda. The ubiquitous lack of access to public records and information is also disconcerting, given the level of corruption at the highest levels of the USVI government.

If I am successful in getting the Legislature to make substantive changes to the sunshine laws, everyone in the Virgin Islands stands to benefit, including the Legislature. Several senators and their staff have admitted that they have also had difficulty obtaining certain records from the executive branch.

Does being a native of the USVI allow you to get things done in ways that a news outlet or advocacy organization from elsewhere wouldn’t be able on its own? Do you think the same principle — that locally led campaigns are more likely to get off the ground — would hold true elsewhere in the country?

Although some people are more likely to talk to me when they realize I am a native of the USVI, being a Virgin Islander has not made it easier for me to penetrate the political system and obtain public records and information. I, like most credible journalists, never want to distract from a story by making it about me. I don’t do this work for my own aggrandizement. However, there are times when you are the subject of the story or your life intersects with a story, and sharing your challenges adds value to a story and may encourage others to come forward. At the end of the day, that is why I became a journalist — to make a difference in society. But speaking up generally comes with a cost, so it is not an easy decision.

I think journalists on the mainland may have an easier time petitioning their government to reform public records laws because it would be easier for them to find community leaders and groups to partner with that are not intertwined with the government. However, independent journalists will face the same challenges that I have unless more media advocacy organizations step up to support them, regardless of whether they work for a big news outlet or not.

Update: This article was revised to replace the main image and modify the caption to add further context.