In response to widespread outrage over the Justice Department’s sprawling leak investigations that engulfed reporters from the Associated Press and Fox News two months ago, Attorney General Eric Holder released long-awaited updates to its guidelines for investigations involving news media.

(Ironically, they were leaked to the media before being officially released.)

First, the good news: protections for most reporters have been strengthened in several key respects.

--A significant part of the Associated Press scandal was the scope of the subpoenas and the fact that the AP was not given advanced notice to negotiate how they were applied. The new guidelines reverse burden of proof, put it directly on the Attorney General, and significantly raises the bar for when the DOJ can delay notifying a news organization of a subpoena.

--The guidelines would prevent DOJ from labeling a member of the news media a “co-conspirator” to justify issuing a warrant for “ordinary newsgathering activities,” largely fixing the Fox News/James Rosen problem.

--DOJ will issue a report to Congress each year indicating how many subpoenas and warrants were issued for information on members of the news media.

-- New restrictions will be placed on how records from media organizations can be used – only in the specific investigation, they can’t be put in a searchable database, and must be stored in a secure location.

-- The guidelines have been updated for the 21st century to ensure the same rules that apply for subpoenaing phone records also apply to subpoenaing digital information from third party Internet service providers.

There is no doubt these rules are significant improvement, but the holes in the rules may be just as significant.

First, these guidelines are just that: guidelines. The oversight procedures are all internal, they do not have the force of law, and there is no clear enforcement mechanism if they are ever broken. As Reporter’s Committee for Freedom of the Press indicated, it’s vital that an impartial judge “be involved when there is a demand for a reporter’s records because so many important rights hinge on the ability to test the government’s need for records before they are seized.”

Critically, there’s also nothing preventing the FBI from skipping over these guidelines altogether and using a National Security Letter to get information on journalists from third party Internet service providers.

But most importantly, these guidelines attempt to define who is and isn’t a journalist. Marcy Wheeler has an excellent examination of the language and definitions used by the DOJ to restrict “members of the news media,” as the DOJ puts it—even as the Privacy Protection Act passed by Congress contains a much broader definition.

Wheeler, who is a widely respected independent journalist, concludes she would not be protected under these new guidelines.

And neither would organizations like WikiLeaks. As the New York Times reported just a few weeks ago, the Justice Department still has a sprawling grand jury investigation open into WikiLeaks, despite the fact that their activities are protected under the First Amendment just like media organizations like the Times. It’s clear DOJ’s guidelines were completely disregarded in WikiLeaks' case and would be again if a similar organization emerged. This is unacceptable if we’re serious about protecting press freedom and not just the established press.

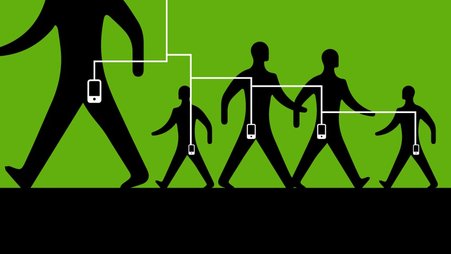

To that point, Harvard Law Professor Yochai Benkler eloquently explained the expanding nature of journalism since the advent of the networked-age in the Bradley Manning trial this week, where he was called as an expert witness to explain how WikiLeaks fulfills an important function. He described how the Internet allows for all sorts of new styles of reporting and called the releases of State Department cables a “high point” in the history of journalism. As CUNY professor Jeff Jarvis empahsized in the Guardian in response to Benkler's testimony, “In this age of radically open networks, journalism is no longer a profession. It is a service to inform society anyone can provide.” Even the Justice Department itself has used a broader definition of journalism in other cases, as Free Press indicated in a letter to Eric Holder.

Many of the shortcomings in the DOJ's guidelines can be fixed by Congress, which should pass a robust shield law that codifies the guidelines, requires judicial review, and applies the law to acts of journalism, not just people they consider “journalists.” Unfortunately, Congress is moving in the opposite direction.

The shield law being discussed contains a massive national security exception, which would make the law useless for the vast majority of federal cases where the Justice Department goes after reporters. As we explained two months ago, in some cases, the law will undoubtedly make it easier for the DOJ to go after reporters. And Sen. Dick Durbin has indicated he believes Congress should define who is a real reporter and who is not.

In an age where members of Congress seem to regularly call for some of the nation’s most respected journalists to be prosecuted, nothing could be more frightening for the future of press freedom.