A recent news report about Secret Service surveillance of former FBI Director James Comey suggests that the Trump administration is abusing its spying powers.

You may remember that the Secret Service and Department of Homeland Security launched an investigation into Comey for posting a picture on Instagram during his beach vacation of seashells spelling out “8647.” Conservatives claimed that Comey’s post was a threat to our 47th president, Donald Trump. Never mind that “86” is slang for banning someone or something, not killing them. There’s also that whole First Amendment thing.

Then, The New York Times reported earlier this month that the Secret Service, as part of its investigation, had Comey “followed by law enforcement authorities in unmarked cars and street clothes and tracked the location of his cellphone” as Comey returned home from his vacation, even though he had already submitted to a phone interview and agreed to an in-person interview.

As the Center for Democracy & Technology’s Jake Laperruque pointed out, that kind of surveillance — real-time location tracking based on cellphone data — generally requires court approval. Although the Supreme Court hasn’t ruled on whether it requires a warrant, several other courts have held that it does.

There’s an important exception, however, to the Fourth Amendment’s warrant requirement. Known as exigent circumstances, it allows for warrantless searches in emergencies. Sources told the Times that the Secret Service invoked that exact exception to justify following Comey.

But Reason Magazine does a good job explaining why that rationale is bunk:

“‘A variety of circumstances may give rise to an exigency sufficient to justify a warrantless search, including law enforcement’s need to provide emergency assistance to an occupant of a home…engage in ‘hot pursuit’ of a fleeing suspect…or enter a burning building to put out a fire and investigate its cause,’ the U.S. Supreme Court wrote in Missouri v. McNeely (2013).

“None of those factors apply here: Comey was on the move, but he was not ‘fleeing’—he was coming home from vacation. If the Secret Service really thought he warranted further scrutiny, it had plenty of time to get a warrant from a judge.”

At least three federal appeals courts have permitted warrantless tracking of real-time cellphone location in emergencies. In one case, a man with a criminal history broke a window at his former girlfriend’s home with a gun and threatened to kill her, her seven-year-old, and other family members before fleeing. In another, a man running a drug operation murdered a potential informant, leaving police concerned that other informants who had infiltrated the operation were at risk. And in the third case, a gang member previously charged with drug crimes threatened to “shoot up” an informant.

These cases are a far cry from posting a picture of seashells on social media. And even if authorities truly believed Comey intended to threaten Trump, he had no way of carrying out that threat at the time he was tracked, since Trump was in the Middle East.

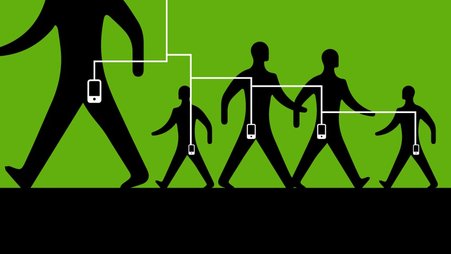

In other words, in Comey’s case, the Trump administration expanded the exigent circumstances exception beyond recognition. But it isn’t the only recent example of the government abusing its power to spy using cellphone data. A recent investigation by Straight Arrow News also detected evidence of a cellphone tracking device commonly known as a “stingray” at an anti-Immigration and Customs Enforcement protest, despite DHS policy requiring a warrant for its use except in — you guessed it — exigent circumstances.

These reports should raise red flags for everyone concerned about surveillance — including journalists and their sources. We already know that the government has tracked at least some physical movements of journalists in past leak investigations. Cellphone location data tracking allows even more all-encompassing surveillance.

If authorities are willing to claim that Comey’s social media post is an emergency justifying warrantless real-time cellphone location tracking, it’s not hard to imagine that they could make a similar (bogus) claim about a suspected whistleblower or a journalist who reports critically on the administration. It wouldn’t be any more meritless than their claims that journalism is inciting crimes or threatening national security.

Concerningly, there’s very little constraint on the government if it decides to abuse the exigent circumstances exception to make emergency requests to cellphone providers for users’ location information. While courts can suppress evidence obtained through illegal searches, they can’t undo the illegal search itself, and officers and officials who abuse the Fourth Amendment face no personal repercussions.

Cellphone providers also seem unable to detect and refuse bogus emergency requests. The three major cellphone carriers — AT&T, Verizon, and T-Mobile — receive thousands or tens of thousands of emergency requests every year. While they require a certification of emergency from the government authority making the request, clearly that process isn’t foolproof if something like the Comey “emergency” can slip through the cracks.

That makes public scrutiny of real-time cellphone location tracking and the government’s reliance on the exigent circumstances exception all the more important. The Fourth Estate — and confidential sources like those who spoke to the Times — may be our most powerful remaining check on the surveillance state.