Donald Trump speaking at the 2015 Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) in National Harbor, Maryland.

More than two years ago, a developer and researcher wants to know what changes the Travel Security Administration (TSA) made to its pat-down procedures at airports around the country. A TSA spokesperson acknowledged changes in a Bloomberg article on Mar. 3, 2017, so days later, Parker Higgins — now Director of Special Projects at Freedom of the Press Foundation — filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to learn more.

It’s almost April 2019, and Higgins has yet to receive any documents responsive to his request. Higgins filed it through government transparency website MuckRock, so he’s been automatically following up on his request every month for nearly two years. At times, TSA has given him an estimated date at which his case might be complete. But the dates fly by, with no real updates provided to the requester.

Higgins is not alone in being kept waiting for documents. The data that formed the basis for an article my colleague Freddy Martinez and I wrote about border agencies’ asset seizures was obtained through a FOIA request that was filed about a year before any records were released. Another requester who filed a request with the FBI in July of 2018 was told that the agency was working on processing requests that were filed in 2016.

Waiting years for disclosure of records through FOIA is not unusual, and it’s not unique to requesters in the Trump era. In rare cares, requesters can even wait decades — like Monte Finkelstein, who requested records in 1993 that he hoped would add to a history book he was writing — only to give up 20 years later and publish his book without them.

For all its flaws, FOIA remains a critical tool for journalists, activists, and community residents who seek to illuminate government activities. But it’s getting harder.

“On a practical level, it’s becoming more and more difficult for individuals—including journalists—to pursue FOIA requests as individuals,” corroborates First Amendment and FOIA attorney Kevin Goldberg.

FOIA: A vital but broken law

On Dec. 28, 2018, the Department of the Interior filed major proposed changes to the way the agency processes FOIA requests. Critics say if adopted, the new rules could make it easier for the agency to deny FOIA requests, take more time to respond, and place a heavier burden on requesters to state even more explicitly to state what they are looking for.

One proposed change could place a monthly cap on the number of FOIA requests each group or individual can file monthly. The Department of the Interior FOIA Policy Office did not immediately respond to questions about the status of these changes, but public records attorneys are concerned.

“Not processing requests that require research is just silly,” said Adam Marshall — an attorney at Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press—on the Interior Department’s changes. “Every request requires research.”

“They are depriving the American people of their right to know what the government is doing — they are only going to cause themselves more fights and more litigation,” Nada Culver, senior counsel at The Wilderness Society, told The Hill.

Marshall notes that ex-EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt’s decision not to proactively disclose his official calendar is another example of the way agency brings unnecessary litigation itself.

“There have been so many FOIA requests for his calendar, which is a basic thing that should have been made available online anyway,” he said “The EPA could have saved itself many lawsuits.”

The Project in Government Oversight (POGO) — a transparency watchdog organization — notes that according to the Trump administration’s own data, the Interior’s FOIA office has seen a 30 percent spike in FOIA requests filed between fiscal years 2016 and 2018.

Departments from the Justice Department to the EPA and the Interior have been hit by huge increases in FOIA lawsuits under the Trump administration.

FOIA lawsuits against the Department of Justice in fiscal years 2001 — 2018

“It’s definitely accurate to say that both FOIA requests and lawsuits have risen,” said open government advocate Alex Howard. “And reasons for that include new technologies like MuckRock, so that it’s easier to file requests.” (The government transparency and news website facilitates a simpler FOIA process for the public, who can file requests through the website’s platform, which automates regular follow-ups on requests.)

“Lawsuits are significant because that’s generally a tell that affirmative disclosure isn’t where it should be, and that FOIA officers aren’t releasing information upon request. It’s a capacity issue, a political will issue, a training issue, and a funding issue.”

Obama and Trump on transparency: Bad and worse

The Obama administration promised to be the most transparent in history, employing lofty rhetoric around disclosure and access. His tone around public records about open governance differed wildly from Trump’s, but some transparency advocates argue that Obama did not just fall short of his goals — parts of his administration worked to ensure his commitments were never realized at all.

On Barack Obama’s first full day in office as president, he issued a memo on FOIA, and called on government agencies to “usher in an era of open government.” He also instructed Attorney General Eric Holder to release new guidelines that would reaffirm the administration’s commitment to transparency. (Many presidents have released memos early in their administrations that clarify how they intend to handle FOIA.)

Holder’s guidelines made central the “presumption of disclosure” at the heart of FOIA, and encouraged agencies to make disclosures of records, and to release them in parts when releasing in full would be impossible.

This presumption is a critical principle that has informed understandings of access for journalists and the public, but the Obama administration also worked to undermine its own publicly-stated commitment to openness.

Behind the scenes, Obama's administration had lobbied to kill reforms to the Freedom of Information Act in 2014 that would have codified these new standards into law — even through they had virtually unanimous support in Congress. The Obama Justice Department opposed the bill , despite the fact that it was based on many of its own policies, and would have codified the very “presumption of disclosure” principle that Obama had declared so early into his administration.

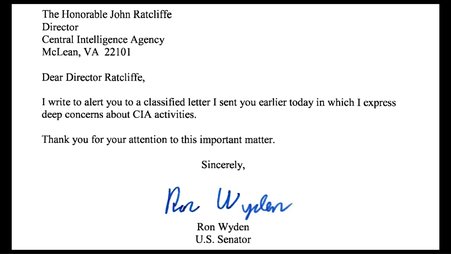

When this became public in 2016 after a FOIA lawsuit by Freedom of the Press Foundation, the administration was forced to publicly commit to signing a similar bill that passed in Congress that year.

Transparency was bad under Obama, but there’s an argument to be made that it’s gotten worse under Trump.

Aside from the meaningfulness of such commitments, Trump did not release any memo on how he expected government agencies to handle public records requests. The Trump administration’s inaction and silence on FOIA speaks volumes. For him, public records and open governance are certainly not priorities, seemingly nowhere on his radar.

“I’m not even sure Trump knows how to spell FOIA,” Goldberg joked. “If you came to him and told him this is how people get information about you and your administration, I’m sure he would explode, and staffers would have to tell him that he can’t do anything about it.”

In some cases, Trump has silently undone transparency mechanisms, catalyzing an erosion of accountability principles. The Obama administration participated in an international open governance partnership (OGP) under which governments like Mexico and South Africa convene to submit plans on how they plan to increase access and openness.

The Trump administration’s plan was due to this coalition in 2017, and the U.S. would have been made inactive in the partnership soon had it not submitted any plan. “It would not be unlike withdrawing from the Paris Accord,” he said. “They are non-binding, but it’s a real withdrawal from public trust in government.”

In February, after years of delays, the U.S. government finally published its open governance plan, which Howard called "notable for its lack of ambition, specificity or relevance to backsliding on democracy in the USA under the Trump administration."

Steven Aftergood thinks that top-level leadership around FOIA and openness, while not everything, matters quite a lot.

“By its nature, FOIA goes against the grain of government bureaucracy, and there is built-in resistance to its implementation. When leaders endorse FOIA and embrace transparency as a value, it can mitigate such resistance—though it does not eliminate it. So even if the Holder memo and similar issuances were not decisive in their impact, they helped to nurture a conversation and to promote a culture of compliance with FOIA.”

“If you don’t at least set the tone, you are certainly not coming to meet any basic bar you’ve set, so there won’t be any initiative from lower down,” said Goldberg.

But even more important than tone and rhetoric, according to Goldberg, is real commitment to transparency at the highest level. “Every agency has limited bandwidth and funding, and a lot of discretion over how they will accomplish their goals, given these limitations. Some prioritize other things, but some prioritize FOIA. And when the highest of levels of an agency say, ‘Our FOIA backlog is embarrassing,’ and reallocate funding and people to get it done,’ that commitment goes a long way.”

And when it comes to the material reality of transparency under Trump, the public is experiencing record levels of government non-compliance.

“People who asked for records under the Freedom of Information Act received censored files or nothing in 78 percent of 823,222 requests, a record over the past decade,” according to analysis by the Associated Press.. “When it provided no records, the government said it could find no information related to the request in a little over half those cases.”

The Trump administration’s FOIA offices’ record levels of censorship provides a reliable indicator on how unimportant he finds transparency to the public.

What's next for FOIA?

Traditional means of obtaining information, such as White House press briefings—in past administrations held every day—are decreasing in frequency. When Trump holds news conferences, he sometimes takes no questions at all, preventing an opportunity for journalists to push back on the president’s lies. Even for journalists at large and well-resourced newsrooms, the tools available to hold power to account are dwindling, and those that remain may be substantially less useful than in previous years.

“News organizations are being lied to, and maybe journalists can’t trust a source, and the government won’t actually tell them what’s happening,” said Alex Howard. “Suits are rising because people are lying to journalists and the public, and the government won’t even offer comment.”

To compensate for a less open government, in which fewer officials answer fewer questions, some journalists increasingly rely on public records.

But if FOIA becomes more difficult and less of a reliably useful tool every year, when each FOIA request is a massive fight that is increasingly likely to require a lawsuit, the number of people that can use it to obtain documents dwindles, too.

Who is FOIA for?

One of the many things FOIA is such a useful tool for transparency is that anyone can file a request for any record that exists at all. Whether a senior New York Times reporter, an early career journalist with a lot to prove, or a concerned citizen, anyone has the ability to obtain government secrets.

Alex Howard brings up BuzzFeed investigative reporter Jason Leopold as a prime example of this. “It’s no accident that BuzzFeed punches way above its weight, according to the organization’s size. Leopold’s success in prying documents is huge. He’s got the receipts.”

With the power of a FOIA request, ideally, a young journalist could launch herself into the world of hard-hitting investigative journalism, and a citizen could obtain evidence of government corruption.

“Current political appointees prefer to operate in secrecy and regard the Freedom of Information Act as a nuisance, not a responsibility,” Jeff Ruch, executive director of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, said in a statement about the Department of the Interior’s proposed changes.

According to several of the transparency advocates and attorneys I spoke to, FOIA will never change meaningfully without an investment of real resources. To do so, they say, will require a true commitment from the highest levels, and, critically, funding.

“How can we improve FOIA and reduce litigation, not by denying requesters the right to sue, but by making it less necessary? How can we build a FOIA that actually works? More staffing, and more training,” emphasized Morisy.

Goldberg says fundamental changes would require “a shift

in leadership, a shift in tone and attitude, and critically an increase

in funding. “We need to think smarter about FOIA, and this

administration, like several prior, has not even begun to think about

what that would look like meaningfully.”

Correction: A previous version of this article confused watchdog organization Project on Government Oversight (POGO) with international openness partnership the Open Government Partnership (OGP).