Legislative Branch records don’t receive the kind of public scrutiny the Freedom of Information Act brings to the Executive, but that could change thanks to a novel lawsuit over video records related to the January 6 riot at the Capitol. If this litigation manages to bring more transparency to Congress, either through a win in court or other pressure, it would constitute a major victory for the public and for the journalists who cover the actions of the government.

This new lawsuit follows an opinion issued by a D.C. Circuit judge in June, which cited a “common law right” of public access to government records that could apply to Congress. In that earlier case, the conservative transparency organization Judicial Watch had sued for access to the subpoenas that the House Intelligence Committee had issued in its impeachment inquiry of President Donald Trump. Although that case was dismissed, Judge Karen LeCraft Henderson wrote in a concurring opinion, “I believe, in the right case, the application of the Speech or Debate Clause to a common law right of access claim would require careful balancing.”

Journalist Shawn Musgrave thinks he’s found the right case. Earlier this month, he sued for the release of the video, citing that "common law right of access.” The primary implications are significant — Congress has some 14,000 hours of surveillance footage from the Capitol on January 6, most of which is not available to the public — but more notably, if successful, this suit could usher in a new standard of transparency for Congress.

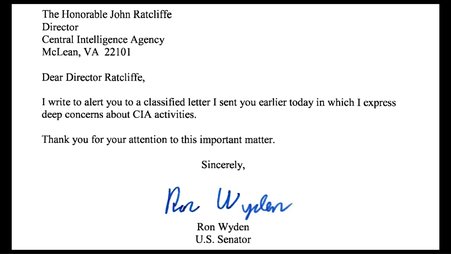

Without a doubt, open records laws — like FOIA and its many state- and municipality-level equivalents — underpin much important reporting. (We capture and highlight some of the stories that rely on those laws with our Twitter bot, FOIA Feed.) But these laws generally only apply to the executive branches of government. Congress, of course, has written FOIA and its many amendments over the previous 50+ years, and has steadfastly refused to apply the transparency law to itself.

As Musgrave's lawsuit contends, there's no reason the animating principle of laws like FOIA couldn't apply just as strongly to the legislature, including Congress. Fundamentally, if the people have a right to know what the government is doing, that right shouldn’t end at the steps of the Capitol.

Somewhat ironically, Congressional objections to increased transparency often focus on the "Speech or Debate Clause'' of the Constitution, which insulates legislators and their staff from arrest or inquiry for statements made on the floor of the House or Senate.

We've written before about how the Speech or Debate Clause represents a woefully underutilized opportunity to share important information with the public and expose government wrongdoing without fear of the draconian consequences that face many other whistleblowers; it's doubly shameful then that the same clause is used in this case to instead obscure the activities of government.

The Freedom of Information Act, and the laws that followed in its image, were revolutionary to the field of government transparency in the 1960s. The law remains vital to journalists, but as Freedom of the Press Foundation and many others have documented over the years, the law is also fundamentally broken.

Like any lawsuit with a novel legal theory, success is far from certain, and could take many shapes — for example, pressure from this lawsuit could and should prompt Congress into taking action with legislation that strengthens FOIA and expands its scope. Still, it's heartening to see journalists and members of the public continue to push the envelope on bringing the activity of the government to the people, and we are eagerly following this effort.