Trust between journalists and their sources is paramount. When first approached by journalists, sources or subjects of stories can often be skeptical of a journalist’s motives—or even question whether they are really a journalist at all. Reporters often find themselves in life or death situations when when speaking with members of armed militias, accused terrorists, government rebels, or in myriad other cases.

So every time a government agent impersonates a journalist to conduct its own investigation, they are putting countless other real journalists at physical risk.

Yet for years, the FBI has engaged in the impersonation of journalists and has defended its practice at the highest level—while keeping its exact policies that govern the tactic. Thanks to documents released as part of a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit by Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, we now know a little more.

Back in 2007, a man identifying himself as a reporter with the Associated Press approached a 15 year old high school student online and asked him to review an article about threats to his school for accuracy. But he wasn’t a real reporter, and it wasn’t real article.

Instead, the man was a FBI agent impersonating a journalist in an attempt to catch a suspect accused of making bomb threats. The faked article sent to the student included malware that revealed his computer’s location and IP address, allowing the FBI to confirm details about the suspect’s identity.

When this became public in 2014, backlash from the press and public was swift and intense. Press freedom advocates and the Associated Press itself raised serious concerns that this tactic could endanger journalists and undermine public trust in news gathering.

"This latest revelation of how the FBI misappropriated the trusted name of The Associated Press doubles our concern and outrage...about how the agency's unacceptable tactics undermine AP and the vital distinction between the government and the press," Kathleen Carroll, then-execute editor of the AP, said in a statement.

Despite the criticism, then-FBI director James Comey defended the agency impersonating journalists in the New York Times, and the FBI’s inspector general also signed off on the controversial practice.

In an even more disturbing incident, FBI posed as a documentary film crew beginning in 2014 in order to gain the trust of a group of ranchers engaged in an armed standoff with the government. The fake crew recorded hundreds of hours of video and audio and spent months with the ranchers pretending to make a documentary.

In response to these harrowing incidents, Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press (RCFP) has been working to uncover the details of FBI’s tactic of impersonating journalists. It is engaged in multiple FOIA lawsuits about the practice—one that relates to the AP case from 2007, and one about impersonation of filmmakers, which led to this most recent disclosure.

This week, after fighting the government for years in court, they finally obtained the FBI’s internal policies for impersonating journalists.

The records show that in order to impersonate a journalist, a FBI field office is supposed to submit an application to do so with the Undercover Review Committee at FBI headquarters and it must be approved by the FBI Deputy Director after consultation with the Deputy Attorney General.

“We’ve understood for a long time that the FBI engages in this practice, so I think it’s helpful for the public to understand the internal rules it utilizes when engaging in it,” said Jen Nelson, a staff attorney at RCFP.

While we know the FBI has impersonated members of the press on multiple occasions, it’s possible that other agencies have also done so as part of their operations. Freedom of the Press Foundation has filed FOIA requests with over a dozen other federal agencies seeking more information.

RCFP continues to work to uncover the details and frequency of the FBI’s use of the tactic, which poses huge chilling effects for journalism.

The FBI’s own arguments in the case acknowledge the chilling effect on journalism presented by this tactic. In a motion of summary judgment obtained by Freedom of the Press Foundation, the agency argued that it should not be required to disclose details about other instances of media impersonation, on the grounds that “it would allow criminals to judge whether they should completely avoid any contacts with documentary film crews, rendering the investigative technique ineffective.”

“That’s our entire point,” said Nelson. “By impersonating members of the media, the FBI causes significant harm to the institution of journalism and undermines the practice.”

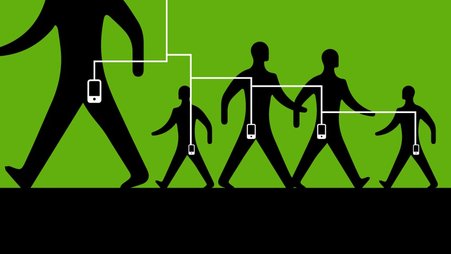

The FBI should immediately halt its use of the tactic, which poses real and significant dangers to journalists, who may have to deal with suspicion of being federal agents while going about their work. And the public also suffers when sources may be more reluctant to bring critical information to the press because they may not know who is a real journalist and who is fake.

If the agency refuses to do so, Congress has the ability to step in and ban the practice by law. Many lawmakers have defended press freedom in the fact of attacks on it by the president, and this would be a powerful way to protect countless journalists nationwide.

Editor’s note: The examples of FBI agents impersonating journalists each occurred in 2014, not 2015 as originally stated. This article was corrected in March 2024.