A protester in swings Mike Kessler's camera before smashing it on the ground, on August 27, 2017, in Berkeley, California.

This past weekend, members of the anti-fascist movement commonly known as antifa organized protests against white nationalists gathering in Washington DC. The anti-fascist crowd overwhelmed and outnumbered the so-called “Unite the Right” rally, and it was a powerful demonstration of using protests to counter abhorrent speech.

As a press freedom organization, though, we have a duty to acknowledge the threats journalists face, wherever they originate. Unfortunately, as has happened at multiple antifa protests since last year, journalists who were covering the event were also attacked by protesters during the rally.

At Freedom of the Press Foundation, we maintain a website called the US Press Freedom Tracker, where we attempt to document all types of press freedom violations in the United States, from illegitimate arrests, illegal searches, harassing border stops, threats from government officials, and the prosecution of whistleblowers.

We also track physical attacks or assaults on journalists. Since the beginning of 2017, we’ve counted 40 journalists that were attacked while documenting protests. Many of these assaults were perpetrated by police officers (including a deplorable incident involving a journalist covering a far right rally this weekend), and we’ve extensively covered unprovoked physical attacks on reporters by white supremacists and right wing provocateurs as well.

Since last year, we’ve also documented over a dozen different physical attacks on journalists or livestreamers covering antifa rallies. Most of them were local reporters assigned to cover a public protest, or freelance or independent journalists trying to document the protests with their own equipment.

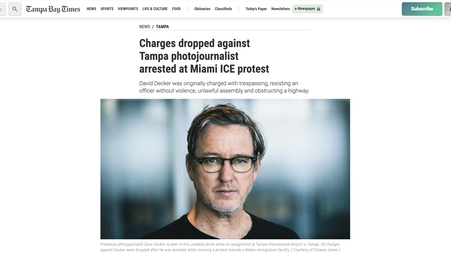

We’ve seen an independent photographer beaten and attacked with a pipe covering a protest in Berkeley, a local CBS journalist in North Carolina attacked with a stick and needed four staples in his head, a journalist for The Hill punched in the head, a Chicago Sun-Times journalist repeatedly punched in the chest, and several cases of cameras being taken or knocked out of reporters’ hands and then damaged or completely destroyed.

Recently, we’ve had multiple journalists contact us unprompted to tell us they’ve felt threatened or menaced when covering such protests. These were reporters sympathetic to anti-fascist issues and did not reach out lightly.

Of course, protests are often messy and chaotic events, no matter which group or cause is organizing them. As CUNY professor Angus Johnston wrote on Twitter on Monday, journalists can get in the way of protesters when emotions are running high. In some situations, reporters have been injured at protests when they were not targeted, and we count them separately on the US Press Freedom Tracker to indicate that fact. There are also many incidents where journalists are screamed at or shoved incidentally, and we do not officially count those as incidents either, even though they can potentially be concerning.

But when journalists are physically targeted when covering a public event, are injured, or have the equipment vital for their job destroyed, it’s cause for real concern. Targeted physical attacks on journalists are wrong regardless of who is doing the attacking, and they should be condemned by everyone—including those in the antifa movement.

Supporters of antifa have sometimes justified these attacks by defending their right to be anonymous while protesting. They have a (legitimate) fear of being “doxxed” or having their personal information posted online by police or white nationalists for participating in a protest, or having their attendance used against them in court. That is why they often wear masks and have the right to do so.

As a First Amendment organization, we strongly support the desire of people to remain anonymous while protesting. In our opinion, the so-called “anti-mask” laws being pushed by some state legislators are unconstitutional, and it’s reasonable that people may want to protect their identity so they can express their political views without fear of consequence for their constitutionally speech. (It’s also why we’ve repeatedly denounced police use of facial recognition, drones, Stingrays, and other invasive mass surveillance tactics at protests).

But protests take place in public spaces; they are inherently public events in which participants attempt to draw attention to a particular issue of public importance. Ultimately, having your photo taken by a journalist is a risk anyone takes when attending any such event. Physically attacking an observer there to document a newsworthy event is a threat to journalists who are just there to do their job.

Others have tried to minimize these attacks on journalists as little more than "corporate property rights." But many of the journalists attacked by antifa have not been employees of large corporations, and are freelance photojournalists struggling to make a living. When activists physically attack them and smash their cameras—which they have often struggled to buy—they are jeopardizing their livelihood.

Regardless, all journalists—freelance or otherwise—have the absolute right to do their job, and exercise the functions of a free press, without unprovoked physical assaults and physical intimidation. At far too many protests, we have seen journalists put in legitimate fear for their safety for no reason other than reporting on events in the public interest.

Condemning physical attacks on journalists is not a judgement on the protest tactics antifa employs, nor is it a condemnation of their political views. Many supporters of antifa also oppose physical attacking journalists covering protests, and many are trained street medics who are quick to jump into action to aid those who have been attacked. For example, journalist Eder Campuzano of The Oregonian, was helped by several protesters after being hit in the head at an anti-fascist rally two weeks ago and other reporters have covered antifa protests without worry.

But we also shouldn’t be afraid to call out disturbing or dangerous acts towards journalists when we see it—even when it’s by groups or causes many people generally agree with.