Law enforcement can no longer claim people have no right to privacy when using a cell phone, and must obtain a warrant to collect historical location data, the Supreme Court ruled today in the long-awaited Carpenter v. United States. This ruling marks a victory for the First and Fourth Amendments, and for journalism.

Writing for the majority, Chief Justice John Roberts explains that the Justices “decline to extend” the so-called third-party doctrine to cover the “tireless and absolute surveillance” afforded by the collection of the near-constant stream of location updates generated by modern cell phones.

Privacy advocates were quick to place the decision in the vein of United States v. Jones, a landmark 2012 opinion that similarly found unconstitutional the warrantless placement of GPS trackers on cars.

As with that case, Carpenter notches a win for press freedom. Although the majority’s reasoning focuses on the Fourth Amendment, the First Amendment implications of a sweeping privacy decision are straightforward: in an era where the government can seize the communications of journalists in the course of investigations into leaks, it’s no stretch to imagine that those journalists’ (or their sources’) location history could also be a target. And as the majority notes, that targeted surveillance can be applied even after the fact:

Moreover, the retrospective quality of the data here gives police access to a category of information otherwise unknowable. In the past, attempts to reconstruct a person’s movements were limited by a dearth of records and the frailties of recollection. With access to CSLI [cell site location information], the Government can now travel back in time to retrace a person’s whereabouts, subject only to the retention policies of the wireless carriers, which currently maintain records for up to five years. Critically, because location information is continually logged for all of the 400 million devices in the United States—not just those belonging to persons who might happen to come under investigation—this newfound tracking capacity runs against everyone.

The government, of course, has warrantlessly tracked people using cell phone location data for years, and was aware of the invasive nature of this surveillance. Still, it argued that the collection was nevertheless legal, even without a warrant. It pointed to the third-party doctrine, a legal premise established in a series of 1970s cases that says individuals lose the reasonable expectation of privacy in information voluntarily shared with third-parties (such as banks in the case of checks, or telephone companies in the case of dialed numbers).

In this case, police used location data from Timothy Carpenter’s cell phone tower records to link him to armed robberies across the Midwest, ultimately resulting in his being sentenced to 116 years in prison. The government argued that the third-party doctrine applied, and so his Fourth Amendment rights were not implicated.

As a legal premise, the third-party doctrine has faced criticism from civil liberties advocates since its inception. But it has been on even shakier footing in recent years. In the aforementioned Jones case about GPS trackers, Justice Sotomayor expressly called its continued application into question:

[I]t may be necessary to reconsider the premise that an individual has no reasonable expectation of privacy in information voluntarily disclosed to third parties. This approach is ill suited to the digital age, in which people reveal a great deal of information about themselves to third parties in the course of carrying out mundane tasks. … But whatever the societal expectations, they can attain constitutionally protected status only if our Fourth Amendment jurisprudence ceases to treat secrecy as a prerequisite for privacy. I would not assume that all information voluntarily disclosed to some member of the public for a limited purpose is, for that reason alone, disentitled to Fourth Amendment protection.

Indeed, the Court today agrees with Justice Sotomayor’s concerns, placing meaningful limits on the third-party doctrine—and critically, placing historical cell-site location information outside of them.

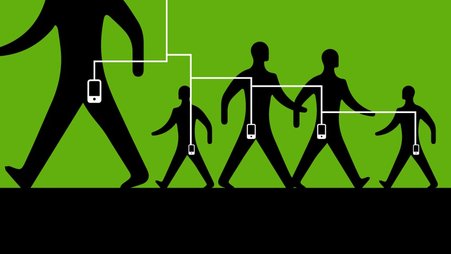

Cell phone location data reveals highly personal and sensitive information—such that access to it provides “near perfect surveillance, as if [the government] had attached an ankle monitor to the phone’s user.” Beyond that, using a cell phone is critical for nearly everyone. Journalists use cell phones to communicate with editors, take notes, and meet sources. As the Court puts it:

[C]ell phones and the services they provide are such a pervasive and insistent part of daily life that carrying one is indispensable to participation in modern society. […] As a result, in no meaningful sense does the user voluntarily assume[] the risk of turning over a comprehensive dossier of his physical movements. [internal quotations omitted]

In these two respects—the sensitivity of location information in particular and the largely involuntary nature of “shared” cell phone information—the majority frames this opinion as a recognition existing limits on the doctrine, not a creation of new exceptions. It explains that in seeking such expansive location data, the “Government thus is not asking for a straightforward application of the third-party doctrine, but instead a significant extension of it to a distinct category of information.” That’s a critically important development, and perhaps the most significant acknowledgment of the doctrine’s limits in its history.

Still, the Court was eager to note that this is a narrow opinion, applying only to the facts in front of it. To the extent that’s true, it is a “narrow” opinion that affects hundreds of millions of people and even more devices. More significantly: it reflects a broader shift in the Court’s thinking on privacy, and—should that trend continue—will bring welcome and widespread ripple effects for privacy in other areas of our digital lives.